Alternative grading cultivates intrinsically-motivated learning

My lessons from being homeschooled as a kid and how I'm bringing those lessons into my classrooms using alternative grading strategies

I didn’t know about grades until high school. Okay, to be more precise, I did know about grades, but I didn’t experience them until high school because I was homeschooled through elementary and middle school. Homeschooling was a great experience for me and had a significant impact on who I am today. It taught me to be an independent learner and to develop a self-starting attitude toward learning without the extrinsic motivation that is so often baked into the academic complex that we expose students to from an early age.

This intrinsically motivated desire to learn has paid huge dividends for me. Helping my students to also grow to love the process of learning has become a central goal of my own work as an educator. I’ll be happy if when I retire I am known for two things: a deep care for my students as whole persons and an approach to teaching that is focused on helping them to develop their own practice of learning motivated by curiosity.

Grades incentivized my desire to compete, not to learn

After finishing elementary and middle school at home, I went to a local private Christian school for high school. It was also an excellent educational environment, but the quality of my education changed and the introduction of grades was certainly a key contributing factor.

When I say the quality changed I don’t mean quality in the sense of the degree of excellence. I had many great teachers in high school. But, nonetheless, the felt experience of my education changed with grades, and not for the better.

When I was homeschooled I didn’t have quantitative measures of my academic achievement: to this day I still have no idea how I performed on the standardized tests that my mom would have us take at the end of each year. I think it went ok except for the year when, if I recall properly, either my brother or I came up with a strategy to quickly fill out the test and get to read the comics in the room next door: just fill out the questions by iterating through the multiple-choice questions in a predetermined sequence of (a), (b), (c), (d). Mom wasn’t thrilled..

But the bigger point is that school as we know it today is not just about learning. It’s also a game. I have a competitive personality, so I enjoyed the game. But this came with some gnarly and unfortunate side effects. Throughout high school, I had a friendly running competition with one of my best friends, Jack. We took pretty much all the same classes and ultimately he came up just short of me in the race for the top GPA in our class. High school was a game and I won. Or did I?

Highschool to undergrad to grad school

During undergrad, I was similarly focused on optimizing my strategy to maximize my GPA. I still felt the pressure to post the highest grades I could to clear the hurdles to get to the next place. Play the game. Score the points. Again, I won. But at what cost?

Sure, I learned and achieved a lot, but what did I lose in the process of constant competition? I still loved to learn, but the flame that burned bright during my years at home during elementary school had been dimmed by the structures and systems of the academic structures of grades. The extrinsic motivation of grades is not the best way to foster the development of learners. The carrot and stick should be the last resort, but we often just go there from the start because it’s easy.

It wasn’t until I arrived at Caltech for graduate school that my attitude toward grades relaxed again. Now I’d finally made it to the terminal degree. At the next stage, people wouldn’t care as much about grades, and the analysis of my work and achievements as a scholar would rest not only on my grades but also on my scholarly activity and contributions to my field.

It’s not that I was uninterested in learning through high school and undergrad. I was! I loved to learn. That love of learning was cultivated in me early on during my homeschool days and no amount of standardized testing or grade point average game-playing could squelch that. But my attention was split. At best, grades were not always aligned with learning. At worst, they sometimes were in direct competition.

From graded to grader

Fast forward to today. Now I’m on the other side of the desk and the one making the grading policies. So, I’ve been thinking: how can I get closer to emulating the experience of learning that I had during my homeschool days? Grades may be an unavoidable part of my work, but how can I find ways to better align my grading practices with my values as an educator?

In my first four years as a college professor, I’ve grown increasingly dissatisfied with the typical grading structure of a course where a student’s grade is determined by a weighted sum of performance on a variety of different types of assignments, exams, and labs. It’s better than no structure at all, but we’re obsessed with quantifying things. We assume that the A-F grading schedule we all are so familiar with has been around since prehistoric times instead of being a mid-20th-century invention.

With this in mind, I’ve been thinking about the grading structures in my courses. A grading scheme is a technology, and as such it comes under the same line of critique that I work to bring to any technology. As I continue to wrestle with it, I’m increasingly unconvinced that a traditional grading structure with set breakdowns between different categories of assignments is the best way to motivate students to achieve the desired learning outcomes in the course.

Over the last year, I’ve been digging into these ideas more intentionally and considering ways to prototype them in my courses. A lot of this is inspired by the stuff that

and write on their excellent Substack and their book by the same name. I’ve also enjoyed reading and her blog reflecting on her experiments with ungrading on . has also been a great source of wisdom about valuing process over product.Today I want to share a prototype I’m running this semester: a new grading scheme that I’m using in my embedded systems class. I hope it will help students not only to learn more effectively but be more closely aligned with helping them cultivate their own intrinsically-motivated approach to learning.

Microprocessor-based Systems (E155) at Harvey Mudd

For this fall I chose to revamp the grading in my upper division technical elective Microprocessor-based Systems (E155). E155 is a relatively small class with a normal enrollment of 25 students and is particularly amenable to trying out some new grading strategies due to its project-based learning format.

In the next few sections, I will explain my goals and hopes for the experiment and what I hope to learn. The rest of the post is structured in three main sections:

What is E155 and how was it previously graded?

Why did I feel that an alternative grading approach would be a good fit?

How do I plan to implement and evaluate my alternative grading prototype?

I’m scheduled to write a reflection post on the experience for

at the end of this year. I hope that this article will serve as a helpful reference to document my intentions at the outset of the experiment.What is Microprocessor-based Systems (E155) at Harvey Mudd

E155 (or MicroPs as it is commonly referred to at Mudd) is broken into two main parts. The first half of the semester is seven labs or mini-design projects. The students complete these on their own time and demo them to an instructor each week.

The content of the labs is focused on a mix of field-programmable gate array (FPGA) and microcontroller (MCU) topics. Then, in the second half of the semester, the students form teams of two and build a final project together.

Students have a ton of latitude for both the labs and the final project. The labs are loosely structured as mini-design projects without much guidance on how to complete them other than certain specifications that the final design must meet. The final project is even more open-ended since the only requirement is that the design must do something fun or useful and meaningfully use the MCU and FPGA. In case you’re curious about the types of stuff they build, here’s a link to the list of final project websites from last year.

The previous grading structure

The previous grading structure was a pretty standard categorical breakdown.

50%: labs

45%: project

5%: class participation

Each lab was weighted equally and graded on a seven-point scale: three points for whether the lab met the specifications, three points for the brief report and accompanying documentation, and the final point assigned based on the student’s response to an oral “fault tolerance question” about a concept in the lab or an aspect of their design.

The project was divided into 5 main pieces weighted according to the following breakdown:

10%: Proposal

20%: Midpoint status report

10%: Design review presentation

40%: Final demonstration

20%: Final report

Each assignment within the project had a rubric with detailed buckets. This was fine...but...I just felt like there had to be a way to make this better.

My main gripes were about the rubrics and the lack of opportunities for students to revise their work. The rubrics had a lot of wiggle room and this was frustrating to students You could say this was just a bad rubric, but the challenge is finding a rubric that is able to fairly assign partial credit when there are many valid ways to successfully complete an assignment. Partial credit as a concept for an engineering system is a tricky proposition. When you’re designing an embedded system, there's often a minimum level of performance that it has to meet or otherwise it's really not useful.

In the previous structure, there were also no opportunities to revise work if it didn’t work the first time. If a lab didn’t meet the specifications the first time around it was no good. Students had a one-week extension they could use, but beyond that not much flexibility built into the grading structure. If they missed an assignment and its learning goals, there was no incentive from the grading structure to go back and try again.

Alternative grading as an approach to address my dissatisfaction

Dissatisfied with the current state of affairs, I was on the hunt for something better. After some preliminary research and perusing different techniques, I picked up Specifications Grading by Linda Nilson. This was a great primer to get me thinking about how to use specifications grading and also had a bunch of examples that were helpful, even though they weren’t directly applicable to my class.

My main takeaways from Specifications Grading were:

How to implement credit/no-credit grading for individual assignments as opposed to offering a rubric with partial credit.

A strategy to bundle assignments together to translate the performance on individual assignments to a letter grade.

This was great! It felt very aligned with the things that I care about and this seemed to be a natural fit with my assignments. I already had in my mind a list of specs that would constitute the minimum acceptable level for an assignment and so I just wrote them down.

On top of this, I also wanted to provide a mechanism for students to demonstrate a level of polish to their work that was above and beyond proficiency. For this, I introduced another, higher level of specifications. These specs describe a lab that demonstrates excellence in understanding and applying the material. Labs in this category demonstrate that the student not only understands the key learning goals but can deftly implement them.

Of course, the proficiency and excellence specifications for each assignment still need to be mapped onto letter grades by the end of the semester. Here's what I cooked up to do that, inspired by the examples in Specifications Grading.

Students earn their grades in the class by submitting a sufficient number of assignments in both the labs and project bundle that meet a certain specification level. At a base level, students need to complete a given number of assignments that meet the proficiency (P) specs. Then, to achieve a higher grade, they need to complete a subset of those labs to meet a higher level of excellence (E) specs.

For example, to earn a C, they must complete at least 6 of the labs to the level of proficiency specs. Of those 6, at least 2 must meet excellence specs. In addition to meeting the requirements for a C in the labs bundle, they also need to meet the project requirements. For a C in the projects bundle, they also need to complete 4 out of the 5 project deliverables to the level of proficiency specs and 2 of those must meet excellence specs.

Co-creating grading structures with students

I knew it was likely that this would be the first time many of my students would encounter this type of grading scheme, so I wanted to make sure that I involved my students in the decision-making process. One thing I love about alternative grading methods is that they naturally lend themselves to aligning the goals of instructors and students.

On the first day of class, I presented this structure to my students in class and asked for their input, gathering their ideas for ways they felt this was a fair structure and ways to better align the policy with my stated goals to help them demonstrate the ability to implement and apply the topics and to have an opportunity to revise their work.

One thing that came up in this conversation was how in-class participation should contribute to the grading policy. In an earlier iteration of the policy, I had in-class participation as a separate bundle with requirements for each row. After discussing in class, we decided that in-class participation should help push you up into a higher classification, but that if a student could demonstrate excellence on all the assignments without attending class, it shouldn't hurt them. Of course, there will undoubtedly be a correlation between in-class participation and performance. But this puts the onus on me to bring material and activities into class that will help students achieve excellence. I'm happy to bear that responsibility.

In-class participation is one piece of information that will be used to fill out the +/- space between grade levels and give evidence to support bumping students up in addition to cases that split the line between categories (e.g., meeting the requirements for a B in the labs bundle but for an A in the project bundle).

Tokens: Incentivizing the achievement of excellence through revision

The proficiency/excellence specs grading approach seemed like a good fit for assessing the learning outcomes for each lab, but it didn’t have a system built in to encourage students to revisit previous assignments in order to revise them based on feedback and to apply what they’ve learned throughout the course to their earlier work. I decided to implement this through a token system. This system helps to encourage revisions while ensuring that students don’t get too far behind and build up a backlog of assignments that they won’t be able to finish in time.

At the start of the class, students get two types of tokens: 1 extension token and 2 retry tokens. The extension token allows them to take an extra week on any individual lab with no penalty. Life happens. This allows flexibility to even out a rough week without giving enough leeway for them to fall too far behind in the class. The retry tokens are designed to encourage them to go back and revise their work to bring it up to a higher level of polish. I hope these will help encourage students who may have had a bit of a rough start to the course to go back and revise and improve their prior work.

We’re currently nearly halfway through the semester and so far this has been working out well. I’m looking forward to reporting back on the full semester in a few months!

Alternative grading is more important than ever given the current changes that AI is bringing into the classroom

As I’ve learned from my own experience growing up homeschooled, intrinsic motivation is much more powerful than extrinsic motivation. Unfortunately, we’ve become increasingly reliant on grades and other standardized markers of competence to help us assess the learning of students and measure their potential to contribute to their chosen field.

While these external markers are convenient heuristics, they fall prey to the inherent flaw of any metric used to reduce the dimensionality of data. It’s the same failure mode that you experience when you take a statistical distribution and describe it with a single measure like the mean or standard deviation. Those measures can help you to describe the distribution, but only if the underlying data actually adheres to the model that you’ve chosen. And even then, you can easily miss important conclusions by looking only at these compressed measures. When we try to do this as we grade human performance, we’re bound to fail and run into all sorts of issues.

Intrinsic motivation is even more important as we enter the brave new world of education permeated with AI. The power of AI enables students to create the product without following the process. It’s sort of like driving to the top of the mountain instead of hiking it. Sure, you get the same view, but you miss the joy, struggle, and satisfaction of hiking to the top one step at a time. Not to mention that you develop a dependence on the tool that may or may not be healthy.

If students don’t understand that the process is the goal, then they’re missing the point and robbing themselves of an experience by skipping to the end product. The point of an assignment isn’t about acing the assignment—and this is almost self-evident if you stop to think about it. The digital systems that my students design in MicroPs don’t approach the level of performance or robustness that they would need to be production-ready in a commercial product. But that’s fine! The point is that the assignment teaches them the process of thought that will give them the foundation to build the skills needed to extend their design to meet the demands of real-world applications.

The impact of AI on education isn’t just about AI-generated writing but its influence on the whole structure of teaching

I’m not arguing that there isn’t a place for using technology to replace processes that are tedious and no longer necessary—there are surely many places where the work we do is not aligned with the flourishing of the humans doing the work. But in the context of academia, when we see assignments that students are trying to cut corners on in order to get the product without the process (e.g., outsourcing essays to an LLM like ChatGPT), it’s likely that those assessments needed to be canned or at the very least restructured a long time ago.

In this respect,

is dead on the money when he argues that ChatGPT can’t kill anything worth preserving. The extent to which ChatGPT motivates educators to reframe these assignments into something, anything, more valuable may be ironically enough its most significant contribution to education, at least in the short term.Alternative grading techniques are going to be an important part of the future of education. Even more so given our current moment and our conversations around AI. I’m encouraged to see the way that my small effort this semester to find better ways to align my assessment with student learning is panning out and hope that I can continue to incorporate these ideas into my courses more broadly in the semesters to come. Stay tuned to hear more reflections at the end of the semester when I have a chance to spend some more time thinking about the lessons I’ve learned and the influence this prototype has had on my students.

Got a comment? I’d love to hear it. And if this post resonated, please share it with a friend or colleague who you think might get something out of it.

The Book Nook

This week I wanted to highlight two books that have helped me in my exploration of alternative grading. The first is Specifications Grading by Linda Nilson. This book was immensely helpful and practical. It helped me not only understand the motivation behind the ideas of specifications grading but also provided several examples of how to implement it in various contexts. While none of those contexts were identical to mine, they provided enough information for me to imagine how the ideas might translate and give me some language for sharing these ideas with my students.

The second recommendation is Grading for Growth by

and . As I’ve already mentioned, Robert and David write a Substack newsletter by the same name () and this new book, released this summer, has likewise been a helpful guide for me to think through alternative grading techniques. I didn’t manage to crack this one open until midway through the fall semester so I haven’t yet finished it, but I’ve been pleased to see the way that they borrowed similar themes from Linda in Specifications Grading and include not only motivating concepts but also specific case studies and examples to help you easily translate these ideas into your own practice.The Professor Is In

This last Saturday I was glad to give a talk for an organization that I was involved with at Caltech during my time there as a graduate student, Science and Faith Examined (SAFE). This time around, I was on the other side of the conversation and in front of rather than part of the audience. I had a great time sparking the conversation with my good friend Kurt Keilhacker and hope that it is the start of many curious conversations about the influence of technology on our lives.

While the event wasn’t recorded, I’m hoping to record a version of the talk to share and will be sure to share that when I get around to it!

Leisure Line

Still blown away by this video (no audio) that I shot on Sunday of a monarch butterfly in our backyard. Check out the way you can see it drinking nectar from the flowers!

Still Life

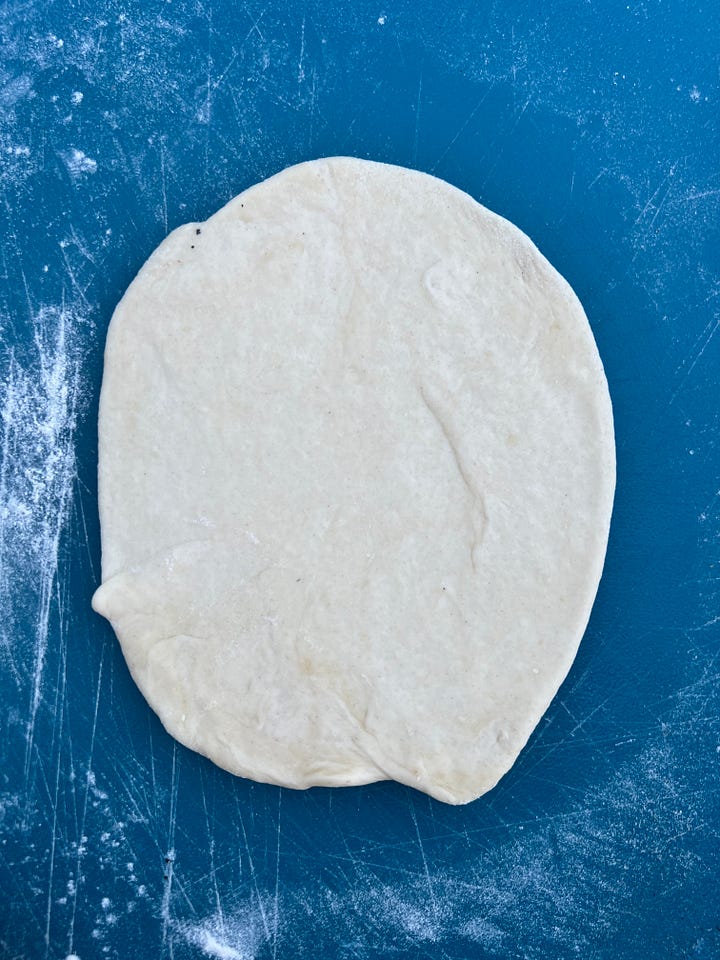

If you thought that pizza was the only thing you could cook in the Ooni, think again. It’s also great for pita or naan bread. Tried out a new recipe from NY Times Cooking (free link across the paywall) this weekend and it turned out great!

Looking forward to hearing how this turns out!