Be Redemptive

Make something the world needs

Thank you for being here. Please consider supporting my work by sharing my writing with a friend or taking out a paid subscription.

There are few mottos more firmly cemented in the Silicon Valley canon than the one coined by Paul Graham for Y Combinator: “Make Something People Want.” But as we prepare for the present and coming deluge of new companies and products fueled by generative AI, we had better consider whether this phrase is robust enough to bear the weight that is about to be placed on it.

I’d argue that it has never been robust enough to guide our work. It’s helped birth plenty of sticky apps and products, but not all of them have been good for us, even if they check the box of being something we want. We’re about to see just how dangerous it is to make satisfying the desires of users the defining mark of success.

We don’t need to make something people want; we need to make something the world needs.

Although I didn’t directly reference Paul Graham’s essay in my post from a few months ago, I wrote some thoughts about his motto a while back in response to some comments from Mark Zuckerberg. Mark, in an interview with Dwarkesh Patel, comments about the opportunity of creating new products with AI, specifically about building AI “companions.”

In describing the problem, Mark comments on a statistic he learned from working on social media. “The average American has fewer than three friends,” Zuck says, “but the average person has demand for meaningfully more.” As Dwarkesh raises concerns about people replacing human relationships with bots, Mark explains his philosophy on evaluating products.

There are a lot of questions that you only can really answer as you start seeing the behaviors. Probably the most important upfront thing is just to ask that question and care about it at each step along the way. But I also think being too prescriptive upfront and saying, “We think these things are not good” often cuts off value.

People use stuff that’s valuable for them. One of my core guiding principles in designing products is that people are smart. They know what’s valuable in their lives. Every once in a while, something bad happens in a product and you want to make sure you design your product well to minimize that.

But if you think something someone is doing is bad and they think it’s really valuable, most of the time in my experience, they’re right and you’re wrong. You just haven’t come up with the framework yet for understanding why the thing they’re doing is valuable and helpful in their life. That’s the main way I think about it.

Who am I to decide?

On its face, this sounds reasonable—humble even! “Who am I to decide whether something is good or bad?” he seems to say. “I’m not in the business of deciding for other people what is good for them.”

Building something people want and using metrics to measure how much they like it might be good for finding product-market fit, but it rests on a certain assumption that what people want is in their best interest and in the interest of the people around them. It’s built on a certain ambivalence about a bigger good, focusing more narrowly on whether it caters to the desires of individual users.

It might sound good, but building with this sort of attitude conveniently avoids the ethical challenges of deciding whether the product that you’re building is actually good for people or just feeds their worst appetites. Not only that, but measuring your work against what people want leaves out any evaluation of the intention behind the product being built (the why) and the way it is being built (the how).

If your experience in the world is anything like mine, it doesn’t take long to recognize that the things we want are not always good for us. I’m reminded of the words of the apostle Paul: “For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.” Our desires and the actions that follow in their wake are not guides worth following.

Is it enough to be good?

It’s interesting to me that Graham coined this motto in a post titled “Be Good.” In the essay, Graham writes that building a business motivated by benevolence—looking to do something good for the world—is a recipe for business success. It gives you power, helps you to build morale for your team, makes other people want to help you, and acts as a compass to help you choose what to build.

Nevertheless, he makes it clear that he is not attempting to write with any moral authority. It’s just that being good is good for business.

So I’m not suggesting you be good in the usual sanctimonious way. I’m suggesting it because it works. It will work not just as a statement of “values,” but as a guide to strategy, and even a design spec for software. Don’t just not be evil. Be good.

However, just because the “usual way” is sanctimonious doesn’t mean that it must be that way. There is a way to suggest that we ought to be good while at the same time recognizing that we will never live up to even our own aspirations for good. There is a way to hold ourselves and each other to a higher standard while recognizing that we will all fall short of it. Just because we can never live up to it, doesn’t mean that it’s not worth pursuing. Being good is not a thick enough mission to guide our pursuits, even if it is practically useful. Neither is building something people want.

We need a rallying cry that points us beyond catering to people’s desires. We need to think not just about individuals, but communities, neighborhoods, cities, and countries, and the world. We need to acknowledge that things are not as they should be; that there is a brokenness in our world that runs through every part of it and, in fact, through each one of us.

Instead of making something people want, we need to make something the world needs.

Pursue the Redemptive

As many of you know, I’m currently on sabbatical from my faculty position at Harvey Mudd. I’m spending the lion’s share of my time with an organization called Praxis, a Christian non-profit focused on advancing redemptive quests. One of the things that drew me to the Praxis community is the way that they not only articulate, but also embody this idea of building what the world needs.

One of the core ways they do this is built on the idea of the Redemptive Frame. Here’s a short video to give you a taste of what redemptive means in this context.

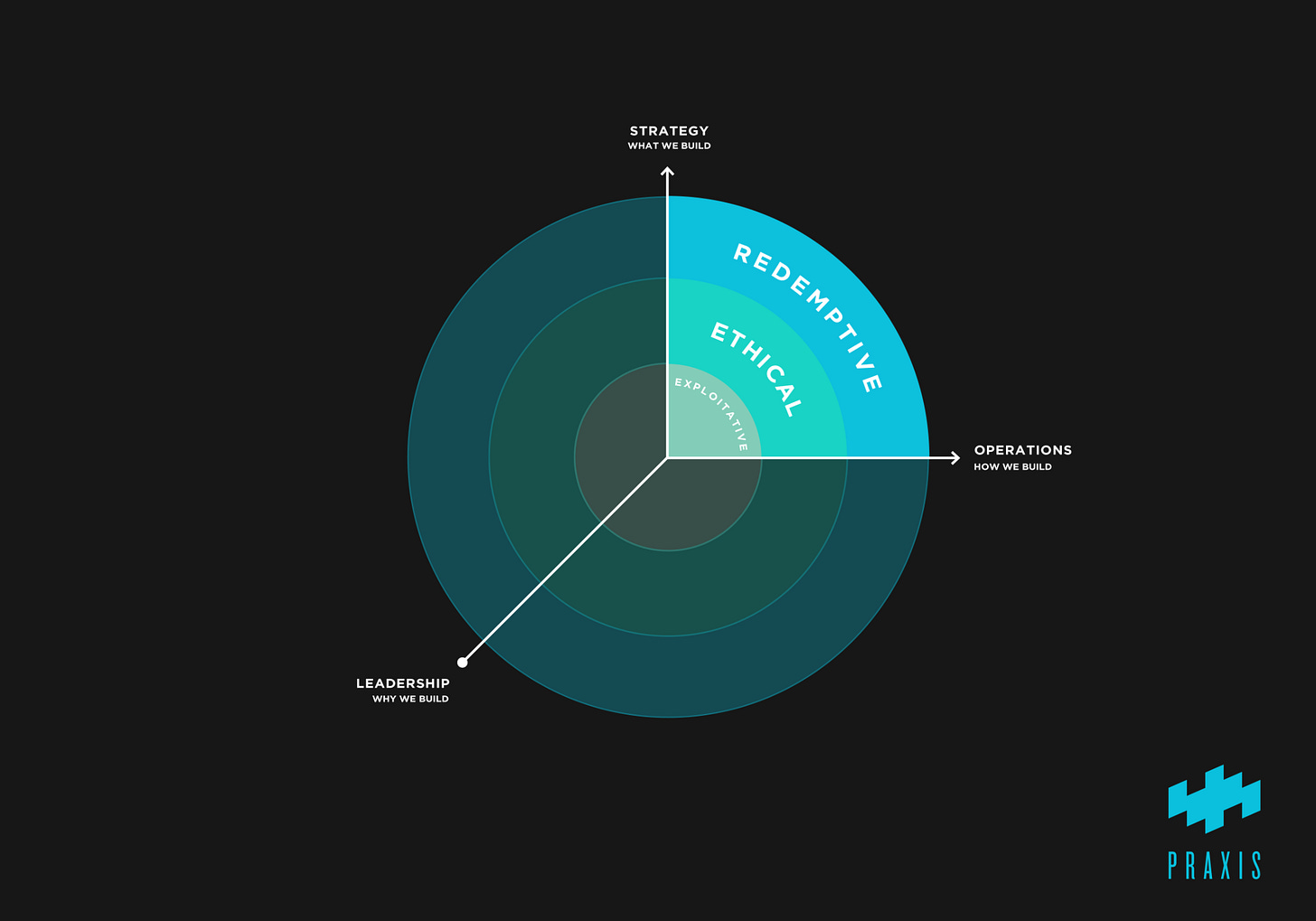

As we unpack the idea of the Redemptive Frame, it helps to portray a fuller and more comprehensive way of understanding the kind of action we need in our world today. It begins by categorizing the way we build into three different modes: exploitative, ethical, and redemptive. At root, these different motives are characterized by three different postures:

Exploitative: I win, you lose

Ethical: I win, you win

Redemptive: I sacrifice, we win

You likely can get some idea of the areas where you’ve seen the exploitative, ethical, and redemptive at play in your own life, but they really come into focus once you consider how these postures interact with the three different dimensions of building: strategy, operations, and leadership.

These three dimensions, represented by the axes, begin to help us unpack what it looks like to actually be exploitative, ethical, or redemptive in our work. These three axes define three different elements of our work:

Strategy: What we build

Operations: How we build

Leadership: Why we build

These three elements provide a holistic view of the things we are building. They help to explain that the things we build are not just about the products, businesses, or services themselves, but the motivation behind them and the resources and people who make them come to life.

When you begin to see the world through this lens, it reframes not only the way we work, but the things we work on. When you seek to build with redemptive strategy, operations, and leadership and build what the world needs, it begins to clarify what the problems are worth working on.

If there’s one thing I can agree with Graham about, it’s that the most important question is the question of what to work on.

But the most important advantage of being good is that it acts as a compass. One of the hardest parts of doing a startup is that you have so many choices. There are just two or three of you, and a thousand things you could do. How do you decide?

In the same way that Graham’s call to be good helps you to decide what to work on, so does the rubric of the Redemptive Frame. But instead of highlighting opportunities to cater to the desires of your users, the call to bless others invites us into a posture of sacrifice—seeing not just the surface-level desires of others, but seeking to understand their deepest needs and to seek their good, even if that means that we cannot maximize our returns or profit margin.

When you start to see the world in this way, different ideas begin to surface. The areas that surface are not opportunities to make the most money or impact the most people, but areas that are in need of restoration and repair. Praxis has organized and named these as Opportunities for Redemptive Imagination (ORIs). These are major issues of our time, issues like addressing political polarization, building new solutions in adoption and foster care, valuing disability as a gift to society, and reversing the mental health crisis.

These are issues that require redemptive strategy, operations, and leadership in order to make progress. They are intractable otherwise.

Whenever we discover or invent a new tool like generative AI that enables us to build more effectively, we will always face a choice. Do we use the leverage provided by that tool to further accelerate progress on products that will cater to users’ needs or to tackle the thorny problems that may have previously been too costly to move the needle on?

Analyzing my own work through the lens of the Redemptive Frame challenges me. It reveals the ways that my own intentions, ambitions, and actions fall short of what it looks like to bless others by putting my own interests and desires second. It challenges me to more deeply pursue restoration and repair and consider the ways that I might better use my resources to build something the world needs. Perhaps it might do the same for you.

Got a thought? Leave a comment below.

Reading Recommendations

I loved this essay from Kevin Kelly from earlier this week. Beautiful storytelling and a reminder of the ways that giving and receiving kindness can shape us.

Kindness is like a breath. It can be squeezed out, or drawn in. You can wait for it, or you can summon it. To solicit a gift from a stranger takes a certain state of openness. If you are lost or ill, this is easy, but most days you are neither, so embracing extreme generosity takes some preparation. I learned from hitchhiking to think of this as an exchange. During the moment the stranger offers his or her goodness, the person being aided can reciprocate with degrees of humility, dependency, gratitude, surprise, trust, delight, relief, and amusement to the stranger. It takes some practice to enable this exchange when you don’t feel desperate. Ironically, you are less inclined to be ready for the gift when you are feeling whole, full, complete, and independent!

I’ve been a fan of Cal Newport for a long time. His call to “Be Wary of Digital Deskilling” was well articulated.

A world in which software development is reduced to the ersatz management of energetic but messy digital agents is a world in which a once important economic sector is stripped down to fewer, more poorly paid jobs, as wrangling agents requires much less skill than producing elegant code from scratch. The consumer would fare no better, as the resulting software would be less stable and innovation would slow.

The only group that would unambiguously benefit from deskilling developers would be the technology companies themselves, which could minimize one of their biggest expenses: their employees.

The Book Nook

I’ve had Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Player Piano on my to-read list for a while now, and finally dug in last week. It is a piercingly insightful glimpse into a world that may not be all that far in our future. It follows the protagonist, Dr. Paul Proteus, the manager of the Illium Works. He lives in a world where human tasks have been increasingly automated and are now performed by machines. As we follow his story, we see him realize what can only be called the spiritual emptiness of the life that he is living as he contemplates what the machines have taken away from his humanity.

One particular paragraph that resonated:

When I had a congregation before the war, I used to tell them that the life of their spirit in relation to God was the biggest thing in their lives, and that their part in the economy was nothing by comparison. Now, you people have engineered them out of their part in the economy, in the market place, and they’re finding out—most of them—that what’s left is just about zero. A good bit short of enough, anyway. My glass is empty.” Lasher sighed. “What do you expect?” he said. “For generations they’ve been built up to worship competition and the market, productivity and economic usefulness, and the envy of their fellow men—and boom! it’s all yanked out from under them. They can’t participate, can’t be useful any more. Their whole culture’s been shot to hell. My glass is empty.”

The Professor Is In

The spring semester is almost here! I’m excited to get moving on the two Innovation Accelerator projects on AI that I’m a part of on campus this semester, working with faculty and students to think about how we might move forward together.

Leisure Line

#1’s winter soccer league started last week and is off to a good start. Evening practices are pretty chilly from the sidelines, though!

Still Life

Caught a few dueling squirrels on the tree in our backyard yesterday morning.

Thank you, Josh. This is so interesting.

I was very blessed to start out the new year by spending some time with my very good HMC Class of 1981 friend Tod Allman and catching up on the groundbreaking work that he is doing using computer technology (a software ecosystem and set of apps which he pioneered some years ago) paired with AI (very recently) to produce full Bible translations of languages with little or no Bible available to its native speakers. Speaking of the sacrifice that is behind this redemptive purpose, notice that this is FREE software which he and his team have to fundraise in order to make happen. I grew up in a family with deep connections to Bible translation pioneers (Jo Shetler often stayed in our home), so I have some appreciation for the importance of my classmate's project, and the fact that he has taken a process that historically required easily 30 years and countless tears, and boiled it down to a few years and a lot of sweat, provided that they find a good mother tongue speaker to work with. Check out https://alltheword.org/ to see his work, and you can even download the software. In my view, this is tech redemptive focus at its best. In our day, Tod and I were behind our class's greatest ever at-school prank; he was the mastermind, and I was the henchman. Today, he is quietly leading the effort to close the gap on eliminating Bible-less peoples in the world. I am very proud of my friend and classmate.