For The Sheer Joy of Climbing

Thoughts on how to prevent AI from robbing you of the value of building expertise of your own

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available. If you are able, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Support from individuals like you enables me to spend more time writing. If you can’t afford to contribute financially, consider sharing my writing with someone you think might enjoy it.

Over the weekend, I stumbled on this tweet from Austen Allred.

My reply? “Sounds a lot like programming.” I think Austen gets this, but I’m not sure the broader AI and education discourse does—especially the folks who aren’t in and around classrooms.

Here's the deal: there's a particular way of working with generative AI that is a lot like eating processed food. It takes something that should require time, talent, and taste and replaces it with a more convenient and efficient substitute. It’s a shortcut. But just like eating processed foods isn't good for your physical health, leaning on AI tools to process your information for you will negatively impact your intellectual health in the long term.

There are lots of things in life like this. We’ve become obsessed with the product and have lost sight of the value of the process. Even if the end is the same, not all paths to get there are created equal.

Magical obsessions

One of the core problems is that much of the conversation around AI is mired in a thinly-veiled desire for magic. This is not by accident. Just take a look at much of the marketing and advertising around it. Today's magic wand is The Button and the prompt is the magic spell.

has written brilliantly about this idea in his latest (pre-ChatGPT, by the way) book The Life We're Looking For. His piece a few months ago in , “Where the Magic Doesn’t Happen,” is also a great read. In so many ways, Andy predicted and prepared us for the AI era by observing the impact that technology has had on us. In short, it's impacted our relationships: with ourselves, each other, our work, and our world.What we’re learning is that the AI magic often isn’t quite what it's cooked up to be. Admittedly, there are aspects that feel magical, especially at first. Large Language Models and the tools built with them can do some truly astounding things. But part of the challenge is the ever-present temptation to hand over the keys. The more we are entranced by the appearance of magic, the stronger the temptation becomes.

The promise at the core is product without process. I suspect, given our expectations, we’ll find ourselves dissatisfied with the results. The fact that the natural use of these tools encourages us to shortcut the process will be a big part of that.

Being a student in the age of AI

My biggest concern is not for the experts who are experimenting with AI in their workflows. There are certainly issues there, but my biggest worry is for those who are working to develop expertise right now. For that next wave of experts in training, there are many dangers. They are being told, whether explicitly or implicitly, that the need to develop hard-won expertise is not the same as it once one. This is a lie.

I wrote a note about this post from Punya Mishra’s blog a few weeks ago, but it’s worth resurfacing here. The question at hand is how we help learners navigate the deception of AI as they move from the bottom left quadrant toward the top right quadrant. What I like about this diagram is that it highlights the specific challenges of each quadrant. There are risks and challenges even if you are a domain expert with a good grasp on the fundamentals of AI.

My central argument is that the best way to prepare for the future is to double click on developing expertise. But the kind of expertise we develop and the way we think about its value must be conscious of AI.

I’m obviously biased, but I am confident that Harvey Mudd graduates will be well-prepared for the future. What makes our program well-suited for an uncertain future is that it prepares students with a broad foundation, both in STEM fields and in the liberal arts. This has served them well in the past and will continue to serve them well in the future.

The hallmark of our engineering program is that we push back against the lure of specialization. Students first take the core curriculum, which equips them with knowledge and skills across the humanities and STEM. Then, when they enter the engineering major, they take classes across the engineering sciences (digital and analog electronics, mechanical, chemical, and materials engineering), design and professional practice, and systems engineering. They exit with a broad foundation and foundational skills across engineering, but most importantly, they see the bigger picture. Fundamentally, they see the world not through solution-oriented lenses defined by a discipline, but driven by a problem.

This is the route that will prepare students to thrive in an AI-dominated world. But it will be in large part not only because of the expertise they’ve developed, but the kind of expertise they’ve built.

Yes, there is value in understanding how AI works. But the reality is that AI is most useful for those who can apply it in an area of pre-existing expertise. It's in this lane that an expert can use generative AI to help them explore new ideas and quickly prototype. But what unlocks their ability is not knowledge about AI per se, but the intuition and critical thinking abilities that they’ve built through the process of developing expertise.

Understanding how to do something without AI is one of the prerequisites for learning how to do it well with AI. Without that pre-existing expertise, how could you even know if the product is any good? Just trust the vibes? You're putting your faith in a tool that by design is chasing statistical likelihood instead of factual accuracy and has been trained to tell you you're right.

The view depends on the path you take

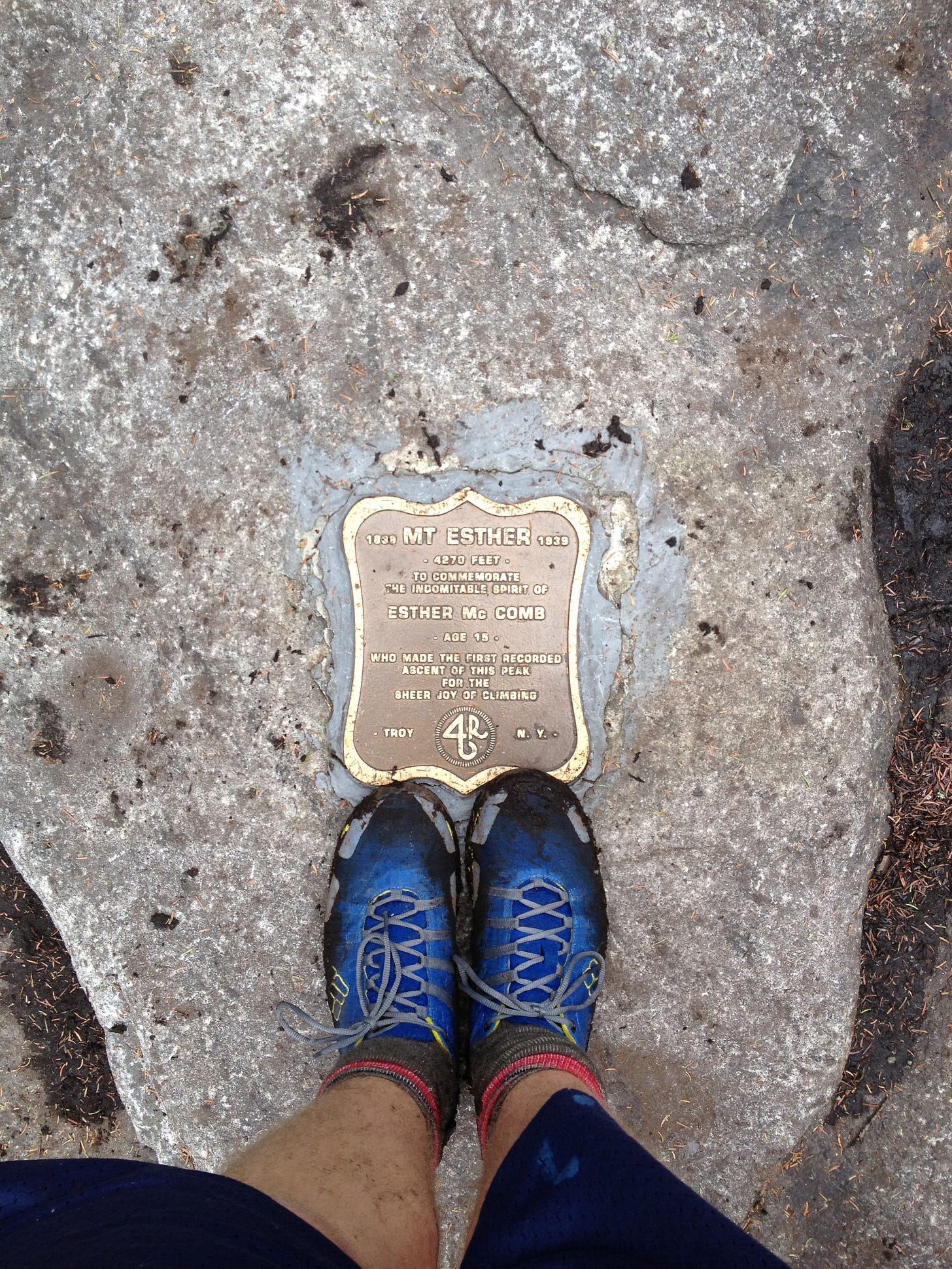

Near the northeast corner of the Adirondack Park, just outside of Lake Placid, NY, lie the two northernmost members of the 46 Adirondack High Peaks, Esther Mountain and Whiteface Mountain.

A little over a decade ago, I climbed those mountains. At the top of Esther Mountain, there is a plaque, placed there by the ADK 46ers, which bears the following inscription: "To commemorate the indomitable spirit of Esther McComb, age 15, who made the first recorded ascent of this peak for the sheer joy of climbing."

It is fitting that if you look south and just slightly to the west from the peak of Esther, you can see Whiteface Mountain. Whiteface, in addition to being one of the 46 High Peaks, is also home to a ski resort and a road that provides access from the bottom of the mountain to the building on its peak.

There's something almost sacrilegious about a mountain with a road to the top. While what you see might be the same whether you hike or drive to the top, I can guarantee you the view is not the same.

There is wisdom for us there as we think about how to engage AI.

As I've written before, take the trail up.

Got a thought? Leave a comment below.

Reading Recommendations

I’ve been following

and his Substack ever since we posted essays with nearly identical subtitles a little over a year ago. This week, he shared some remarks from a recent keynote he gave. Andrew is certainly more optimistic about the impact that AI can have on education than I am. While I don’t wholeheartedly disagree with what he’s written, I do have some points where I see things differently. Much of this is likely rooted in the answer to the first question Andrew poses: “What does it mean to be human?” For me, this is the central question in the age of AI. If we want to think about the future of being human, we’ve got to start by thinking about the past. At any rate, I would encourage you to read Andrew’s remarks, if for no other reason than it might spark your curiosity and help to crystallize some of your own questions.This week

challenges us to think about our vision of repair. Fitting words for our time.writes an excellent summary of OpenAI’s most recent image generation feature. It’s hard to imagine that the disregard for intellectual property and copyright could get any more flippant. First Johannson’s voice, now Miyazaki’s style.Breaking, as a course of action, requires little more than bluster and bravado. It is motivated by anger, by outrage, by vengeance. (By the way, all of these are repudiated by Christian faith and commitments, or at least strongly cautioned against.) It seems to me that breaking is the soup du jour, whether we’re talking about American foreign policy or evangelicalism or purity culture or political protests on Ivy League campuses. Tear it all down, burn the bad to the ground! Quite frankly, I’m growing so impatient with the valorization of breaking, a campaign that turns out to be far more juvenile than mature. If you want to break something, you can do it in a moment. But if you want to build? For this you will need long-sighted patience. You will need the capacity to cooperate, to give yourself to projects that endure beyond your moment, even your lifetime. You will need vision, and you will need hope.

The Book Nook

This week I started reading Filterworld by

. In it, Kyle talks about our experience of seeing a world that is mediated through algorithmic sorting and filtering. I’m only a chapter or two in, but am already appreciating Kyle’s insights.As the cybernetics pioneer Stafford Beer argued, we tend to use machines to automate the structures and processes that already exist, which were human creations to begin with. “We enshrine in steel, glass, and semiconductors those very limitations of hand, eye, and brain that the computer was invented precisely to transcend,” Beer wrote in his 1968 book Management Sciences, pinpointing the paradox. As with the Mechanical Turk, the human persists within the machine.

A joke written on Twitter by a Google engineer named Chet Haase in 2017 pinpoints the problem: “A machine learning algorithm walks into a bar. The bartender asks, ‘What’ll you have?’ The algorithm says, ‘What’s everyone else having?’ ” The punch line is that in algorithmic culture, the right choice is always what the majority of other people have already chosen. But even if everyone else was, maybe you’re just not in the mood for a whiskey sour.

The Professor Is In

I’m back in the saddle in E85, our digital design and computer architecture engineering science class. It’s a truly wonderful class that takes students from zeros and ones, Boolean algebra, and simple logic gates and digital building blocks, all the way up to building their own simple RISC-V processor core.

Leisure Line

Like a phoenix rising from the ashes. Prime is on point with their pizza box art, as always. And the pizza? Just as good as always.

Still Life

Stumbled on these beautiful African Daisies while on a walk this week. Even caught a bee up close and personal. The quality of macro photos on my iPhone never ceases to amaze me.

As always, I enjoyed your thoughts and your thinking. I even did a bit of research into Esther McComb and her accidental ascent in 1839. I can identify with getting lost and discovering wonderful joy. My views about using AI continue to be a journey. I appreciated Mishra's quadrant illustration because it forces one to look beyond the simple yes/no. My latest thinking (included in my Substack post yesterday) led me to propose what I am currently calling a "Universal AI Proficiency Scale". It looks at the variety of levels of proficiency with AI along a continuum from Novice to Distinguished and also across six different use cases.

Your sentence: "the reality is that AI is most useful for those who can apply it in an area of pre-existing expertise" intrigued me because my expertise in so many places has been increased by the use of AI -- sometimes that expertise was already fairly developed, in other cases it was merely germ-sized -- and AI was the key to helping it blossom. I would hate to think I need to wait until I'd developed "expertise" to use the very tool that could help me develop it.

The Novice's Dilemma in Mishra's diagram would be Novice Low in the Scale I mentioned, but it could be a starting place , IF it were seen and recognized as such.

I'm beginning a walk of another 150 miles of the Camino de Santiago. As with exploring AI practices, uses, and pitfalls, it's all a journey. I'll take the spirit of Esther with me, intent on being open to new ways of seeing the world around me.

Excellent analogy, climbing the mountain or driving there. The journey not the destination.