Get In Touch with Your Inner Hedgehog

To build a career that counts, focus on the intersection of your passion, talent, and what creates long term value

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available without a paywall. If my writing has been valuable to you, please consider sharing it with a friend or supporting me as a patron with a paid subscription. Your support helps keep my coffee cup full.

If you’d like to support my work financially but can’t commit at the $50/year level, you can use the button below to subscribe at a lower $35/year tier.

The path to a flourishing life is a disciplined one. But discipline for its own sake is not enough. We must apply our discipline well, saying "yes" to the right things and “no” to the wrong things. The tricky part is that many of the wrong things are almost right things.

What we need in addition to discipline itself is a strategy to know how to apply it. Today I want to talk about a framework that can help with this and that I'm prototyping this year: Jim Collins' Hedgehog Concept.

At the start of a new year, many of us are taking stock of the last one and thinking about our hopes and desires for the new one. This year, I happen to be reading Jim Collins’ classic, Good to Great which is providing an interesting perspective on my new-year planning. In the book, Collins and his team of researchers break down the secret sauce powering a collection of companies that broke through from good to great performance, delivering value at a level that far outstripped their peers. While he focuses on companies, the concepts are also worth applying in the context of individuals as well.

Collins' core thesis in Good to Great is centered on an overarching idea he calls the flywheel effect. The flywheel is the iterative process that builds momentum and drives value creation. It is powered by discipline in three areas: people, thought, and action.

Collins argues that first we need to focus on the who, not the what. This is the recognition that people are the lifeblood of any organization. Not only must you have the right people in the organization (“on the bus”), but they need to be in the right roles to contribute effectively to the work. After getting the right people on the bus, the next step is to shape the way those people think, helping them to build the right patterns of mind and the organizational culture to sustain those mindsets. Finally, once they are equipped with these mindsets, they will be prepared to take disciplined action in the world.

While Collins' analysis is focused on companies, there is a lot that we can learn from adapting his findings to our individual pursuits. For example, while the "who" in the context of an organization is about the members in it, reframed in the context of your personal quest, you might ask the question in reverse: “What bus do I want to be on and who do I want to be in the seats around me?”

Finding the answer to that question is critically important. While you may have some idea, you need first to understand yourself. What seat might you be well positioned to sit in? How are you best equipped to contribute to a broader vision of change you want to see in the world?

To answer that question, I want to focus on one big idea that Collins introduces: The Hedgehog Concept.

What is it like to be a hedgehog?

The intellectual foundation of The Hedgehog Concept can be traced to an ancient Greek parable that says: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing." In developing The Hedgehog Concept, Collins “yes, ands” this to argue that focusing on "one big thing," was a key driver for the companies that went from good to great.

So what is the one big thing? Well, it’s different for each company, but despite their different sectors, each company’s one big thing answered three questions. Collins illustrates this with a Venn diagram where the circles represent the answers to three questions:

What are you passionate about?

What can you be the best in the world at?

What drives your economic engine?

The secret, Collins argues, is found at the intersection of all three circles.

A hedgehog in the flesh

When I think about The Hedgehog Concept applied to individuals, I can't help but think about Cal Newport. Cal is a dynamo. (If you don’t believe me, just take a quick peek at his website or CV.) In addition to his day job teaching and running a research group in the Computer Science department at Georgetown University, Cal has written a number of best-selling books. He also is a contributing writer for The New Yorker and hosts The Deep Life podcast, a project he started during the pandemic which is at 334 episodes and counting. The man is a machine.

Cal has himself written about his approach to building a flourishing life. I see this most clearly articulated in my favorite book of his, So Good They Can’t Ignore You. In it, Cal argues that a successful career is built not by following your passion, but by building career capital—rare and valuable skills that give you leverage in the market and enable you to construct a meaningful career. Developing these skills is costly but ultimately a worthwhile investment.

Cal Embodies The Hedgehog Concept

While Cal is certainly an outlier—how many of you have signed your first book deal while still in undergrad?—there are still things we mere mortals can learn from his approach. The Hedgehog Concept framework can help provide a lens to analyze Newport's choices and offer a suggestion about how we might use it in our own lives.

What Cal has done is identify his ability to be the best in the world at making sense of productivity in a way that doesn't focus on the hacks or shortcuts that treat the symptoms but ignore the underlying causes. Instead, he offers a diagnosis of the underlying disease and an antidote to the condition that creates the symptoms we see on the surface.

His superpower, or at least one of them, is articulating ideas that can help us embody sustainable practices to achieve our long-term goals. His books over the last few years (Deep Work, A World Without Email, and Slow Productivity) have all been grappling with different aspects of what it means to embody the Navy Seal's motto: "slow is smooth and smooth is fast."

While it's unlikely that you (or I) have the raw talent and brainpower that Cal runs on, his life is an example of the Hedgehog Concept in practice: Cal is laser-focused on the intersection of his Venn diagram. I can only imagine the number of interesting opportunities and potential directions that he's said no to so that he can stay the course and double down on those few areas where he wants to have decade-scale impact.

But what about passion?

Those of you who have read Newport may have a question at this point. What about Collins' circle about passion? Doesn't Newport reject passion as a guide for helping us build career capital?

It's here that putting Collins into conversation with Newport has given me a deeper understanding. It helps to reinforce a point that Newport makes but might be missed unless you’re paying attention to the nuance of his argument. It's not that passion is bad, it's just that it cannot be the sole driver of our career aspirations. It's not enough to love to do something, it must also be something you can be world-class at and that will create value in a way that generates the economic output to make your work sustainable.

A mentor of mine recently posted a quote that feels relevant here: "Entrepreneurs radically overestimate what they can accomplish in a year, and radically underestimate what they can accomplish in ten." I’d argue that this applies to almost all of us—we’ve got to dream at the appropriate time scale. Most of us get this wrong.

This idea also reflects the reality of the hedgehog: if you find the one big thing at the intersection of your passion, talent, and value creation and then consistently keep at it, you’ll be surprised at what you can accomplish in a decade's time. The accumulation of effort over time matters in more scenarios than we realize.

The real unlock of The Hedgehog Concept is that it lives within the iterative container of the flywheel. Starting from a standstill, you've got no momentum. But, given the right community of people and structure of disciplined thought, even a little consistent effort can begin to build and build as time goes on. What begins as a crawl turns to a walk and eventually hits a smooth, running stride. Although perhaps for a hedgehog a smooth scurry is the best we can hope for.

The key, as you likely already know, is to start. This year, let’s embrace the hedgehog way.

Got a comment? I’d love to hear it.

Reading Recommendations

This week Andy Crouch wrote an excellent essay for Jon Haidt’s Substack After Babel on magic and technology.

If there are two kinds of magicians in the Western imagination, Faust who clings to magic and Prospero who renounces it, there are also two kinds of magic. One, the magic of the alchemists, is the quest for domination and control of nature and whatever powers may lie beyond nature. But there is another magic, best captured by the idea of the enchanting—the sense, often unbidden and seen only out of the corner of our eye, that something wonderful, awesome, majestic, and mysterious is afoot in this world, something for which control is simply not the right word, indeed something which we would not want to control for fear of diminishing its beauty and its goodness. If the quest for the first kind of magic drives a prideful quest for power, the second kind of magic produces in us something much closer to humility.

Two weeks and two Sacasas posts! I was delighted to see yet another L. M. Sacasas essay in my inbox this week. In this post, Mike reflects on the delightful experience of a cat painting he encountered while on a walk with his children and uses it as an opportunity to explore the difference between human art and AI-generated content.

The Book Nook

One of the underrated parts of being a parent is having a socially accepted excuse to revisit children’s literature. This week I had fun reading Stuart Little to the kids at bedtime. Now we’re on to Mr. Popper’s Penguins and James and the Giant Peach.

The Professor Is In

The last few weeks have been a much-needed respite from the constant push of the semester. I’ve been glad for the space and time away, but am also glad to be getting geared back up to see everyone when classes start on the 21st!

Leisure Line

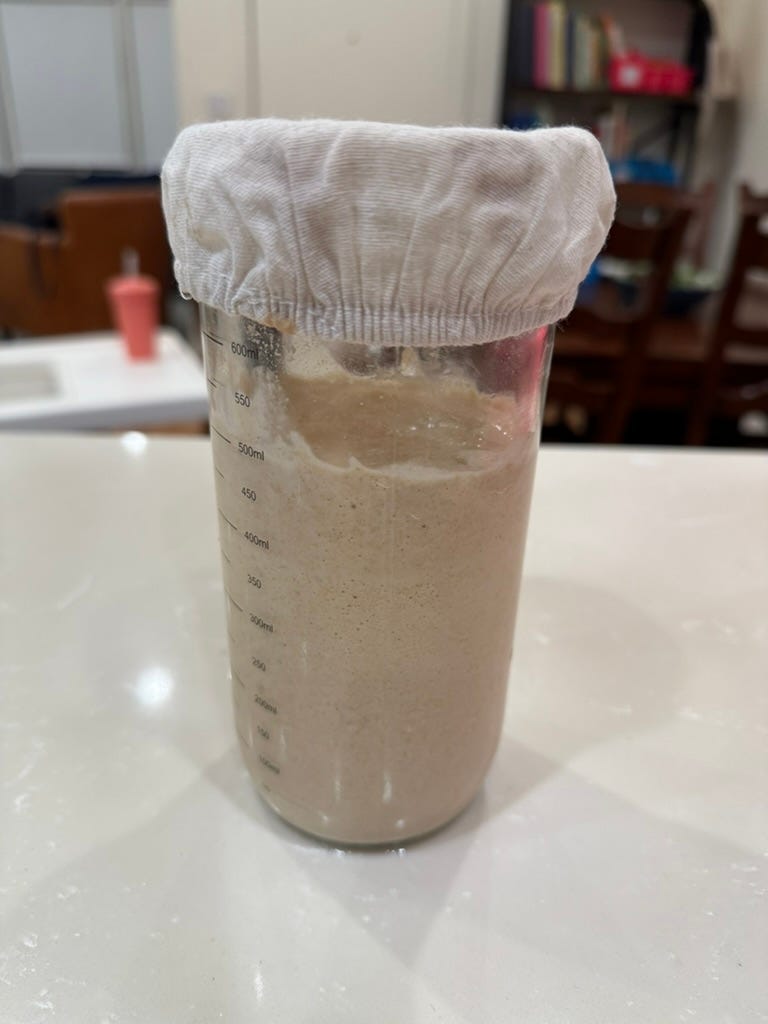

My wife’s family does a Secret Santa gift exchange every year and this year, mine gave me a kit of sourdough bread-making supplies. And so, the new experiment of this holiday season has been nursing a sourdough starter to life—tricky to do given the relatively cool temperatures

Still Life

One of the hallmark events in Pasadena each year is the Rose Parade. The local’s secret is to go at 11 pm the night before to see the floats all lined up on Orange Grove Blvd. Always fun to see the last-minute preparation happening overnight. This year’s adventure was getting caught behind a bunch of floats in traffic on my way down Fair Oaks Avenue (see the first picture in the gallery).

Ha! I still remember reading Stuart Little, Mr. Popper’s Penguins, My Father’s Dragon (and others like them) to my son almost 30 years ago. Still have them on our bookshelf…

I see a discrepancy here which is that you are advocating for the hedgehog concept, yet you teach at an institution that does the exact opposite. Not only is this evidenced by Harvey Mudd's core curriculum and humanities requirements, this is also exemplified by the engineering department (where you teach) which requires students to take engineering from a variety of disciplines instead of focusing on one, as with most colleges.

This would seem to imply that either 1. you think that the kind of liberal arts education that Harvey Mudd provides is lacking in some way and cannot provide the value that the hedgehog concept provides or 2. you think that the liberal arts framework is compatible with the hedgehog concept.

If 1 is the case, I would like to know, what is missing/how can we improve the liberal arts education?

If 2 is the case, I would like to know, how is liberal arts compatible with the hedgehog concept?