Postman’s Prophetic Provocations

Five essential insights for the builders of tomorrow

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available without a paywall. If you can, please consider supporting my writing by becoming a patron via a paid subscription. Your support helps to make this work sustainable.

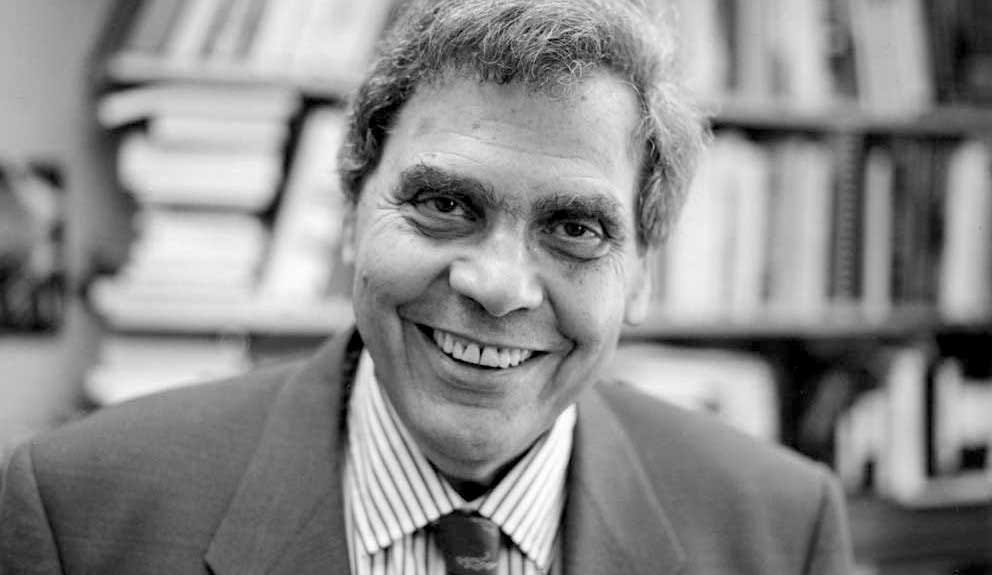

It is hard for me to name a single thinker whose ideas have taught me more about the societal impact of technology than Neil Postman. There are others around the table of my mind that are in the same category—thinkers like Marshall McLuhan, Ursula Franklin, and Jacques Ellul alongside more modern writers like Sherry Turkle and L.M. Sacasas—but Postman is, for me, in a class of his own.

I'm sure part of it is that Postman was in many ways my gateway to this conversation. Reading Amusing Ourselves to Death opened my eyes to entirely new ways of understanding technology. It's one of those books that fundamentally changes the way you see the world. That book, and the McLuhanist mantra "the medium is the message" is essential for anyone trying to understand the world around us today. Not only that, but Postman's work is critical for the builders of tomorrow like the budding engineers in my classrooms who will be part of creating the technologies that shape our future.

When training builders we spend a lot of time talking about what and how to build. We look for market opportunities and problems to be solved, using them as fuel for our creative engines and design processes. What we don't often spend much time talking about are the personal, economic, and sociological dimensions of why we build.

As we shape the future, we need to carefully understand and align the what, how, and why. We have a mandate to build—the brokenness around us should compel us to build in order to alleviate suffering and make the conditions for flourishing more accessible for everyone. But building in a way that will help to promote our flourishing requires careful consideration.

Postman is of great help in this quest to build and live with technology in more thoughtful ways. In addition to the long-form arguments in his books, Postman also gave a number of speeches where he condensed ideas that can help us better understand technology and technological change. One particular talk that has been helpful for me is a set of remarks Postman delivered in 1988 titled "Five Things We Need to Know About Technological Change." In it, he explores five insights about technology that every builder and user of technology needs to know:

All technological change is a trade-off.

The advantages and disadvantages of new technologies are never distributed evenly among the population.

Embedded in every technology there is a powerful idea, sometimes two or three powerful ideas. These ideas are often hidden from our view because they are of a somewhat abstract nature. But this should not be taken to mean that they do not have practical consequences.

Technological change is not additive; it is ecological.

Media tend to become mythic.

For the remainder of today's post, I will present Postman's five ideas, with additional commentary about how they help us understand our present moment and the technology of generative AI that is defining much of our discourse about technology today. But before you read my commentary, I urge you to read Postman's comments directly. If your experience is anything like mine, those five pages will forever reshape the way you see the role of technology in our world.

1. All technological change is a trade-off.

When we think about new technologies, our minds naturally dwell on all of the new opportunities they create rather than thinking about the negative consequences. The phrasing of "unintended consequences" is often a euphemism. These consequences are not so much unintended as unconsidered, and often intentionally so.

We also tend to ignore that new technologies shape society and the built world around us in ways that not only prevent us from opting out but compel us to opt in to certain behaviors. This is connected to Postman's fourth point about the ecological nature of technological change. Consider how many of the services in our world are increasingly accessible only through an app on our smartphones. New technology does not simply create new opportunities, it removes the possibility for others too.

My favorite articulation of this idea is Andy Crouch's framework of the Innovation Bargain. In addition to my post about it, you can learn more about it directly from Andy here. Technological innovation is always a tradeoff.

2. The advantages and disadvantages of new technologies are never distributed evenly among the population.

This observation pairs well with the previous one. Not only does technological innovation involve tradeoffs, but the costs and benefits of those tradeoffs are not evenly distributed.

As someone who sees technology as a way to create new opportunities for human flourishing, I think about this a lot. An honest accounting of history makes it clear that in most cases, technological innovation serves to make the rich richer and leave many behind. There is certainly an element of trickle-down benefits, so this is not to say that the users of technology are not positively served by technology, but we must grapple with the fact that technology is ultimately a lever to extend our abilities. Those who hold the reigns and control the development and implementation of new technology naturally reap the most benefit from it.

Not only are the advantages tipped toward those who control new technology, but the disadvantages are disproportionately borne by those who are not in positions of power and influence. As we consider the societal impact of a specific technology, we must consider who is reaping the rewards and who is bearing the costs.

3. Embedded in every technology there is a powerful idea, sometimes two or three powerful ideas. These ideas are often hidden from our view because they are of a somewhat abstract nature. But this should not be taken to mean that they do not have practical consequences.

Another way of phrasing this point is to ask a question: to what question is this technology the answer? We so often see only the end product or "solution." But as we think about new technologies, we must first consider what question it was designed to answer and decide whether we agree with this problem definition. The right answer to the wrong question is the wrong answer.

This is even more important when we are faced with slickly coordinated marketing campaigns meant to create in us an appetite and need for something new in order to convince us that the latest and greatest is a need rather than a want. The storytelling and design behind not only the products in our technological ecosystems but also the marketing campaigns are often specifically designed to create the desire for something we did not ask for. All of this is part of convincing us that adopting new technologies is an inevitable part of progress.

The notion of progress assumes that we are heading in a direction we want to go. Absent an agreed-upon direction "progress" may in fact be taking us in the wrong direction.

The creation of new products may indeed be inevitable. Our acceptance and thoughtless incorporation of them into our lives need not be.

4. Technological change is not additive; it is ecological.

All five of Postman's comments are relevant to our current conversations about AI, but this one may be the most timely. We must not fall into the trap of thinking that we can simply add AI into our workflow in a way that the rest of our work remains unchanged.

Whenever we begin integrating a new tool into our workflows, this shapes the way we do the rest of our work. This happens at multiple levels, shaping not only the specific processes through which we work but the high-level objectives and values of our work as well.

To highlight a relevant non-AI example, consider the way that the calculator shaped the practice of mathematics. The message in the medium of the electronic calculator is that the work of mathematics is primarily about computation. Talk to most students studying mathematics, especially before they experience calculus, and this ecological change will become readily apparent. It's not that the calculator specifically prevents us from viewing mathematics as a broader discipline of inquiry and a way of thinking, but the specific design and capabilities of the tool shape our imagination and culture around the practice and understanding of mathematics.

As we consider how to understand AI, we should be wary of the way that new AI tools have more significant and long-reaching influence on our lives than might be apparent at first.

5. Media tend to become mythic.

When Postman writes about technology becoming mythic, he is identifying the way that technologies, once created, embody a particular narrative in our world. Postman's example of the alphabet is a good one. It is hard for us to even imagine what a world before the alphabet could look like. The same can be said of many of the fundamental innovations that we take for granted today like electricity, the Internet, cities, and agriculture.

As we look down the barrel of the technological innovation spurred by AI, we are likely to see this story play out once again. In the same way that those of us who grew up in a world where the Internet "just was," my children and grandchildren are likely to see the widespread integration of artificial intelligence in a similar light.

As I reflect on Postman's insights, I'm reminded of the power of his provocations. I hope that like me, you'll be challenged by Postman's work and find ways for these questions to shape your own thinking and action when you approach technology, either as a builder or user.

Got a comment? Leave it below.

Reading Recommendations

First up this week is a great piece that I stumbled on after publishing my essay from last week titled “Ethics Won’t Save Us From AI” by R. J. Snell in The New Atlantis. In it, he argues that we need to recover the idea of hope in rather than hope that. Snell’s essay is a response to an essay from Brendan McCord, founder of the Cosmos Institutepublished earlier this year.

The New Atlantis is quickly becoming must-read material for me. If you are interested in technology and society I would highly encourage you to consider adding it to your media diet. Here is a quote from the end of Snell’s essay that is resonating with me.

If we are to use philosophy to shape the human future, we will have to do so not as rational subjects but as humans, who, whether we know it or not, live according to a vision of what is good.

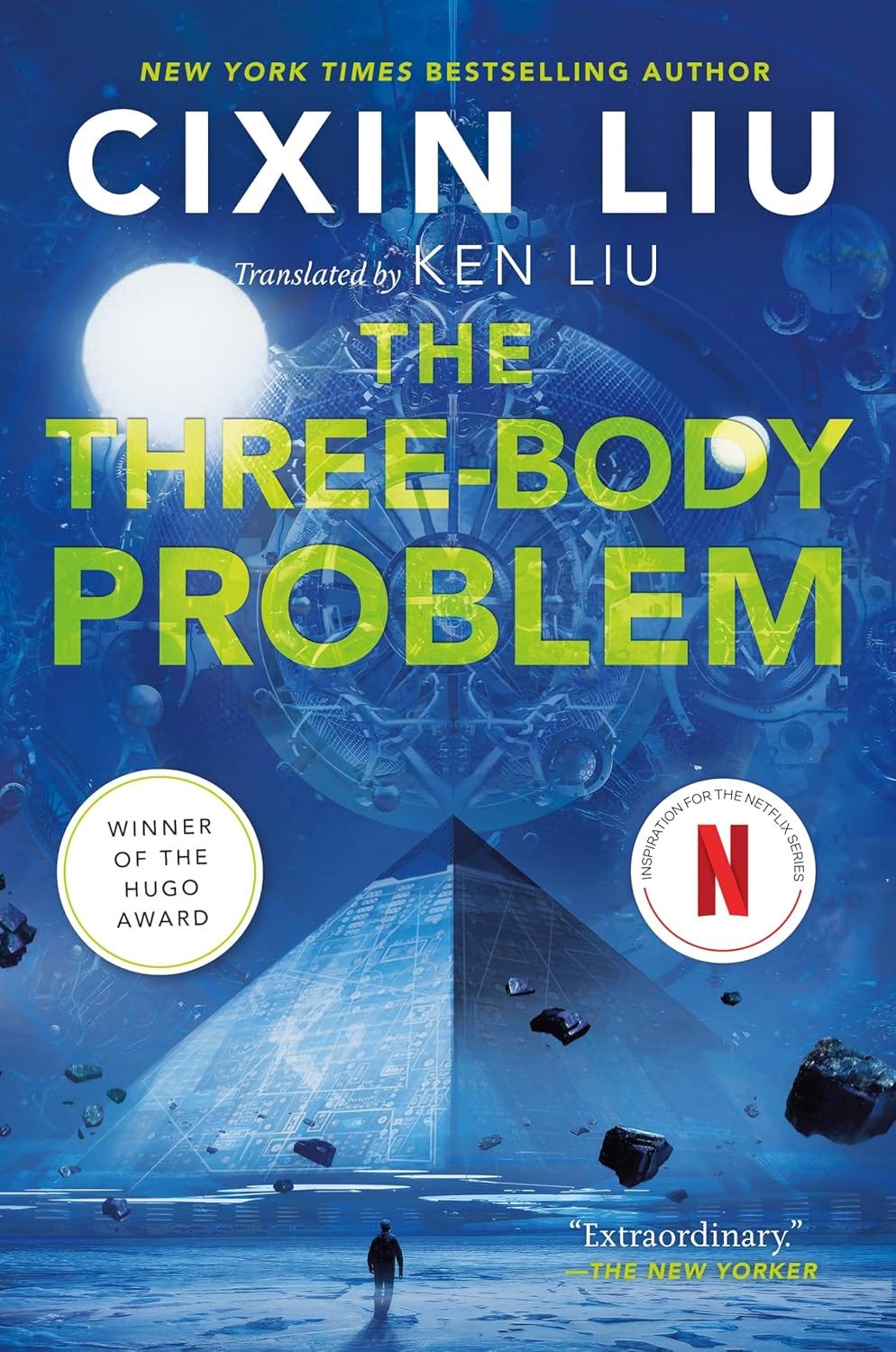

The Book Nook

Update: I’m now just over 70% of the way through. The plot has continued to develop in interesting ways. Hoping to finish it this week!

The Professor Is In

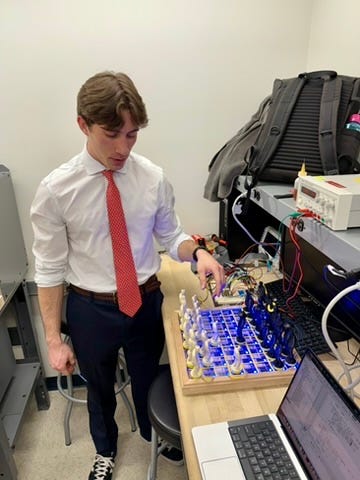

MicroPs demo day was last Friday and boy did we have a good time. At the end of the fall semester, each of the students in my embedded systems class gets to show off their end-of-semester projects.

Here's what they cooked up this year:

🖌️ Digital art drawing on a VGA display. The MCU takes in inputs and sends the information over to the FPGA which renders pixels on the display. Zoe Worrall and Jordan Carlin

🏋️ A system to sense your posture and help you improve your squatting form in the gym. It uses IMUs to estimate the angles of various parts of your body and nudge you in the right direction. Jason Bowman and Ket Hollingsworth

💿 A custom DJ deck that streams data from an audio analog-to-digital convertor using the I2S protocol on an FPGA and then uses the on-board MCU digital-to-analog convertor to output it to speakers with the ability to digitally filter the signal. Audrey Vo and Martha-Victoria Parizot

🔦 A light controller for the DMX interface, commonly used for stage lighting. They used a bunch of sliders to control the different parameters. Avery Smith and Henry Heathwood

🐀 A 3d-printed model of Remy from Ratatouille that you can control by moving your arms. The team uses IMUs to sense the angle of your arms and then moves Remy's accordingly. Alisha Chulani and Marina Ring

💪 A hands-free arm wrestling game that uses electrodes to sense the tension in your flexed muscles and then displays the results on an LCD display. Ellie Sundheim and Daniel Fajardo

🖥️ An image processing system that implements an edge detection algorithm on an FPGA and outputs the results on a VGA display. Troy Kaufman, Vikram Krishna, and Joseph Abdelmalek

♟️ A smart chess board that interfaces with magnetic pieces and shows you the available moves when you pick up a piece. Max De Somma and Luke Summers

🎵 A system to help you correct your pitch when singing. It samples an audio signal and uses the digital signal processing capabilities on the MCU to process the audio wave and determine the frequency. Jackson Philion and Zhian Zhou

🔴 A physics simulation with colliding pixels that move around based on how you tilt the LED matrix It drives a 64x64 LED display with the FPGA and uses the MCU to interface with accelerometers. Stephen Xu and Xiyuan Liu

The students all did great work. For their reports, they're sharing their projects on portfolio websites. You can find more information about the course and the project on the project page of the course website. I’ll share their portfolio websites next week once they’re live.

Leisure Line

Gotta love Porto’s. The best chocolate chip muffins I’ve ever had.

Still Life

Did a little sightseeing in New York yesterday before my afternoon meetings. Took a walk down to Hudson Yards to see Vessel and then took the High Line down south to see Little Island. Then on the way back to my hotel, I stumbled on Tom Otterness’ “Playground” which looked familiar from a visit to Pittsburgh where there is a similar installation.

Postman has forever shaped how I think about media and technology via Amusing Ourselves to Death. I wasn't aware of this talk and appreciate your link and commentary.

Never mind Postman. WHICH Porto's??