Reframing the Disruption of ChatGPT and AI on Education

Mapping a way forward using the examples of the calculator, Wikipedia, and Google search

Conversations about AI have continued to swirl in the world of education since the release of OpenAI's large language model chatbot tool, ChatGPT, at the end of November last year. Reactions span the gamut from full adoption and optimism that perhaps this tool can serve as the push we needed to make our writing classes better to bans and worry as teachers wonder how their courses and assignments will be impacted.

As I've been chewing more on some of my initial thoughts from a few weeks ago, the question that has been stuck in my head is “what is uniquely new about ChatGPT and its impact on education?” Before we decide how we should respond, it's critical that we ask the right questions.

While the uncanny capabilities of ChatGPT are in many ways unlike anything we've seen before, this doesn't mean we don't have a playbook of how to address it as educators. We've seen similarly disruptive technologies before—what can we learn from how we responded?

This week, I want to develop a framework for how we might think about responding to ChatGPT by looking at several technologies that have had similar impacts on education before: the calculator, Wikipedia, and Google. Analyzing ChatGPT through the lens of each of these technologies and the response from the educational community can give us insight into how we might understand the impact of ChatGPT and the other AI tools that will inevitably follow in its wake.

Ultimately, I want to argue for three takeaways from this analysis:

Make ladders, not crutches.

Take AI output with a grain of salt.

Mind the algorithm and its pathologies.

The Calculator: Make sure the tool is a ladder, not a crutch

The first example that came to mind is the calculator and its impact on math education. I remember my trusty TI-84 graphing calculator in high school and learning how to use and program it to perform calculations that would otherwise take much longer by hand.

But even with its relatively widespread adoption then, there were still situations in which calculators were banned. For example, there were portions of the AP Calculus Exam where calculator use was disallowed. Why? To prevent an unnecessary dependency, creating the need for a crutch when one has two perfectly functioning legs.

However, the flip side of this argument is that some calculations are difficult, time consuming, or nearly impossible to perform by hand. In these cases, the use of the calculator is less like a crutch, and more like a ladder. In instances where using the tool enables you to do something you couldn't otherwise do, there is a convincing case to be made for adopting it.

So we learn a first lesson about how to incorporate a disruptive technology: aim to strike a balance that ensures that students know the fundamentals, but also train them to use the technology effectively to extend their capabilities.

Wikipedia: Knowing the reliability of a source matters, but it isn’t the whole story

The second vignette that I find helpful when thinking about how we should engage ChatGPT in the classroom is Wikipedia. The initial pushback on Wikipedia in academic settings was reasonable. Primary sources are important when you’re writing and in many cases Wikipedia is at best a tertiary source, providing an incomplete and sparsely cited summary of a topic.

And yet, my sense is that the pendulum of opinion on Wikipedia has been swinging back toward the middle in recent years. It seems to be approached now with a practical lens, and by my best estimates, is now viewed as a reasonably accurate first place to start your research. The feedback of the communal editing process has turned out to be much less dangerous than initially thought, although exceptions exist especially on controversial topics.

The main lesson to be learned from Wikipedia and its adoption is that we can incorporate a resource even if it is not 100% reliable if we are careful to keep its relative authority in mind. Just because a source is not authoritative doesn't mean it isn't useful, just that we need to make sure we exercise the appropriate amount of caution when referencing it. So, we start with Wikipedia for a summary, but quickly take a look at the linked resources to deepen our understanding of the topic. It's essentially the zeroth order term in a series approximation.

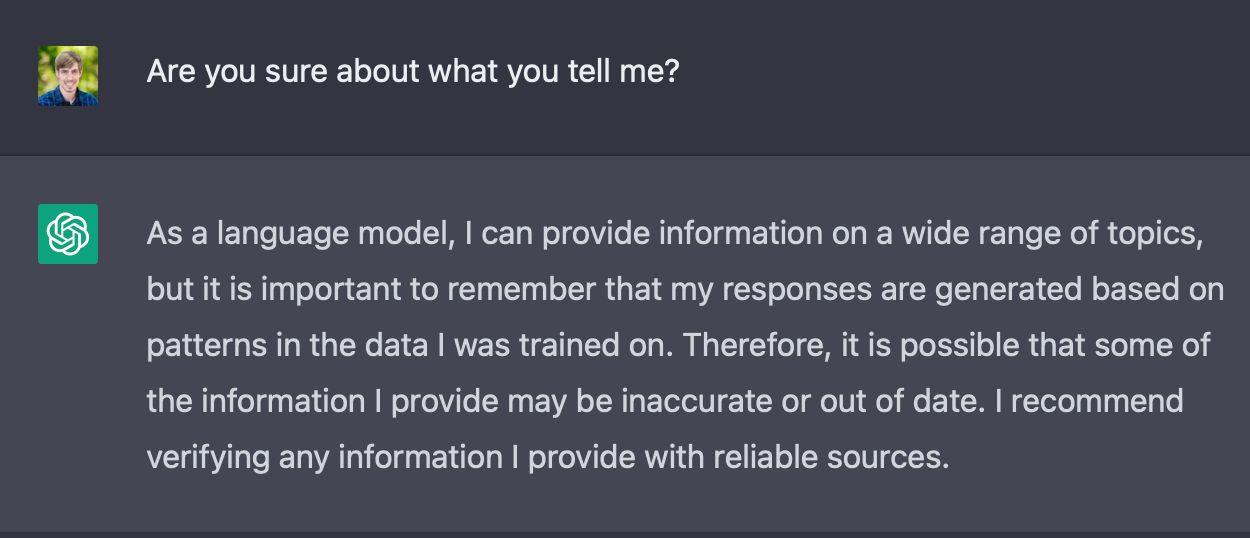

With direct application to large language models like the ones that ChatGPT is built upon, one challenge that has become apparent is the relative lack of nuance and (over)confidence in its responses. Hear it from the machine itself:

Regardless, if we are aware and cautious of its potential to present even clearly incorrect facts as gospel truth due to gaps in its training data, we can take advantage of the rough draft and correct any errors. The key is that we need to be careful to adopt an appropriately skeptical perspective even if the tone of the output signals confidence.

Google: Be wary of the hidden algorithm

The third example to consider when assessing how to adopt ChatGPT is Google search. The introduction of Google search drastically shifted the way that we find information, from guided expertise (e.g., by a librarian or content matter expert) to an algorithm (PageRank).

This is significant for two reasons: (1) the algorithm itself has its own metrics for how to rank the value of a source that are independent from human intervention and (2) our interaction with the algorithm makes the way that we ask a question important. Both of these are also important when we think about ChatGPT.

The impact of the algorithm

First, the algorithm does not think for itself, but simply performs (an albeit sophisticated) pattern matching process to draft its replies. As always, garbage in, garbage out. We've seen how this has played out in other algorithm-driven applications on the web like Facebook Newsfeed or Twitter timeline, and the results often leave much to be desired, pouring gas on the fire of our most divisive tendencies.

Folks have already seen this pop up in different ways on ChatGPT when it is asked to make moral judgments. While we all have our own implicit biases, the tendency of the algorithm to surface these and combined with the overconfidence problem discussed above (doesn't seem like the AI often expresses doubt) makes for a perfect storm that we should be wary of.

The impact of query phrasing

The second impact is that the way that we ask a question matters. Folks have known that there is an art to writing good Google searches for a while, but prompt crafting is critically important to get the highest quality responses out of ChatGPT. In many ways searching Google is less dependent on the specific language you use, although certain tricks can be helpful (e.g., putting quotation marks around words or phrases that you want to appear for sure in the results).

ChatGPT is also distinct from a simple search in that a large part of unlocking its full potential is to use it properly to iteratively craft responses. For instance, you might ask it to generate ten ideas and then ask it to expand upon the third item in the list. Or ask it to draft a paragraph but then add more supporting or examples or caveats.

Compare this to a Google search which is essentially a single step operation. If you don't like the output, you start from scratch and modify the search terms. In this way, each search is its own atomic operation.

So what?

Of course, the million dollar question is where do we go from here? Do we try to ban AI tools in our classroom or totally embrace them? Or is the best approach somewhere in between?

As I wrote a few weeks ago in some of my initial thoughts on ChatGPT, I believe that all pedagogical decisions should be decided by what your learning goals are and then those decisions should be clearly communicated to students along with the rationale for making them. This idea of transparent teaching is one of my core values as an educator.

If I was forced to take a side, I think that in most instances we ought to thoughtfully embrace AI tools, doing our best to make sure that they are being used as a ladder and not as a crutch. Our students will be surrounded with them in the months and years to come and will need to understand how they work and their areas of relative strength and weakness.

Many teachers have been charting the way and sharing their work along the way. Ethan Mollick, a Professor at the Wharton School of Business at UPenn, is one of these trailblazers, writing about his experiments with AI on Twitter and on his Substack. I've also been inspired by John Warner and his provocative take that "ChatGPT Can't Kill Anything Worth Preserving". When it comes to writing, I think this is basically right. The case may be more nuanced for other practices like programming, but even there ChatGPT is in many cases simply replacing other crutches like StackOverflow instead of creating a radically new category of tool.

The bottom line

AI tools will break some existing pedagogical structures, just like the calculator broke some assessments in mathematics. It will require us to train our students to exercise wisdom and a healthy dose of skepticism for the text it outputs. We'll also need to train students how to properly use the tool by crafting prompts and dialoguing in a way that will make the most of what it can output.

In the end, AI is another tool in our toolbox and it is up to us to make sure we use it properly. It's not morally neutral, but just like a hammer can be used to drive nails or to smash windows, we do have control over how it is used. The question we need to answer is how do we best train ourselves and our students to use it? But that question is bigger than just AI.

Resources for Digging Deeper

Here are a few links to interesting articles that I’ve been reading recently on AI and education if you want to explore more.

The Book Nook

Stolen Focus by Johann Hari has been on my list for a while. In this book, Hari explain what he sees as twelve main causes of our current attention crisis. He spends some time highlighting the steps that we can take as individuals to improve our focus, describing his reflections after a technology and Internet detox in Provincetown, Rhode Island. Ultimately he makes the case that individual effort is not enough. Thus, stolen focus.

What I appreciate most about this book was the way that Hari presented a nuanced argument for the various individual approaches to improving attention but also drew attention to the larger, systemic issues at play. I saw a lot of parallels between this and Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism that I read a few years ago. While individual effort is important, we often fail to see the environmental factors around us. Ultimately, reclaiming our ability to focus will require effort in both areas.

The Professor Is In

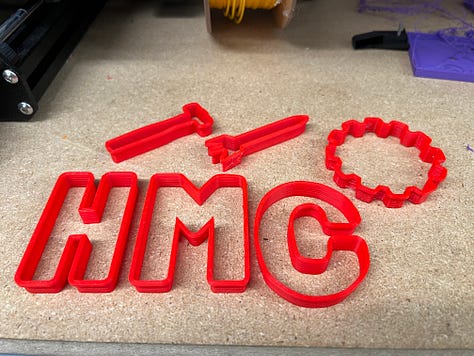

With the start of the Spring semester we launched E80 last week. To celebrate after the kickoff presentation last Friday, we decorated sugar cookies made with custom, 3d-printed E80 cookies.

This week students jumped into their first lab where they built their autonomous robots and launched them in the tank to test them out.

Leisure Line

A beautiful flower spotted on a sunny Saturday last weekend at the LA Arboretum.

Still Life

Love seeing the snow-capped mountains when I come into campus these days.

I agree with your balance of utility and healthy skepticism.

I suppose that the debate over ChatGPT and its many successors and copycats will rage on forever. My concern goes back to when laptops began to become prevalent in school, what with autocorrect and seemingly unlimited access to plagiarism bait at the literal tips of one's fingers. The real debate is certainly even older than all that. Simply, why are we teaching fewer and fewer students how to write well? I could barely read by the time I reached the 6th grade, but when I graduated from Mudd, I had learned to overcome my literacy deficit and went on to acquire decent writing skills as one of the greatest assets that I ever gained from my undergraduate education. That skill has grown over the decades, and it wasn't through making all these terse Internet posts. I look at kids today and am truly sickened that we continue to manufacture button pushing dummies (my brother's term so very long ago) at such an alarming rate. The last advice I was ever able to give to a high school student who was trying to impress some UC school with his application essays was to put down the laptop, pick up a pad of paper and a pen, and start writing -- then I would help him with what he wrote. I'm currently working on a friend's screenplay and am about to do just that very thing myself.