Walking Backwards Into The Future

How exactly do we build a better future? It starts with the humility to recognize that we can only see the past.

Later today, I’ll share a few words at Harvey Mudd’s Fall 2025 Convocation. Here’s what I’m going to say.

If there is one thing we talk about at Harvey Mudd College, it's our mission statement. Even you first-years in the audience who have only been on campus for a few days have surely heard it referenced many times. In fact, I bet you could almost recite it by this point. But in case you’re still a little rusty, here it is once again:

Harvey Mudd College seeks to educate engineers, scientists and mathematicians well versed in all of these areas and in the humanities, social sciences and the arts so that they may assume leadership in their fields with a clear understanding of the impact of their work on society.

Like any good mission statement, this one sentence encapsulates what we do and why we do it. I can only imagine how much time went into drafting this one sentence—time well spent, given how often we recite it!

Over the past six years that I've been part of the Harvey Mudd community, I've heard lots of folks talk about the mission statement. What has interested me most in those conversations is a small but important modification they often make to the last phrase. That change is to address what I sense many of us feel is a bug in the mission statement, namely that it doesn't articulate a stronger moral stance, that we should train leaders who will have a positive impact on society.

I certainly agree with the sentiment, and I'm sure most of you do too. Of course, we want to do good in the world. This is, after all, the theme of our gathering today: STEM for a Better Future. But before we think about what it means for STEM to be part of a better future, we first need to ask: what exactly is a good future?

In the next few minutes that we have together, I'll make a case that what the mission statement does not say is as important as what it does say; that stopping short of saying that our goal is to have a positive impact on society is in fact an important statement about what it actually means to have a positive impact on society.

This is a lesson that I believe a STEM liberal arts education is uniquely qualified to teach us. It's a lesson that is vitally important for all of us scientists, engineers, and mathematicians to learn, whether we are just starting on that journey or have been practicing in our field for many years. It's a lesson that is important for all times and situations, but is particularly salient in our own moment as we see the way that technology is dramatically reshaping our world.

The Future as a Decision Tree

First, let's set the stage.

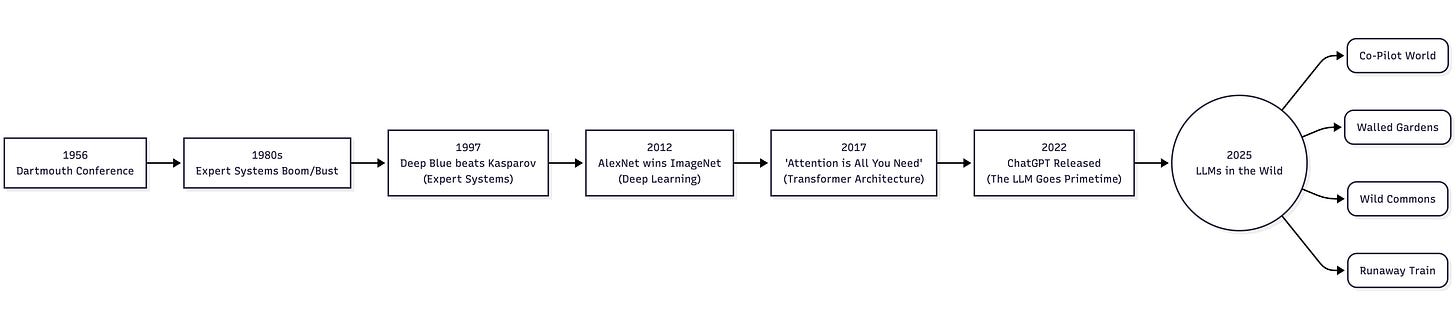

One (admittedly nerdy) way to think about the future is as a decision tree. Obviously, this is a simplistic way of thinking about it, but I find the mental model helpful. Many of you are likely already familiar with the basic structure. A decision tree is composed of nodes and edges, which continue to propagate and expand from left to right as time moves forward. In this model, the nodes indicate significant milestones or events, and the edges have probabilities to represent the likelihood of moving from any one node to another.

It doesn’t take long to see that this diagram is most interesting on the right-hand side, in the yet-to-be-determined future rather than on the already-decided past on the left. Although there are interesting postmortems that can be done on past "what if" scenarios, the tree leading up to this point is a bit boring, since only one branch gets taken, and the rest wither and die. When a certain future is actualized, all of the other probabilities collapse to zero.

The much more interesting question is looking forward. The space to the right-hand side, the future, is yet to be resolved. The probabilities are still live.

If we want to be part of a better future, we'll need to think about the potential branches that exist from our current node in the tree. We'll need to engage our full selves in considering what those potential futures might be, and then build a moral framework for assessing which of these potential futures we want to see actualized and direct our energy toward making that future reality.

What is good?

But if we want to create a better future, there is a big question we have to grapple with: what exactly is a better future?

Rather than try to give you a rather unsatisfying five-minute crash course on philosophy and ethics, I hope you'll offer me the freedom to paint with broad strokes in a way that might help to spark your imagination and encourage you to dig more deeply into these questions over your next four years in this community.

As you can probably already tell, I'm a pretty big fan of questions. The right questions are way more valuable than the correct answers. While answers tend to be brittle and valid only for a specific set of conditions, the right questions are much more robust and valuable as they help to ground and guide you even in the midst of ambiguity and uncertainty.

So here are a few questions that are central for us right now:

What does it mean to be human?

What is our vision of the good life?

What does it mean for us to become good?

How should we grapple with the implicit bargains of our inventions?

How might we understand the impact of our work on society?

These are important questions for Mudders because while in one sense technology is morally neutral, a deeper look will quickly shatter our hopes of any comfort in such a statement. Indeed, while the tools we create may not be good or bad, neither are they truly neutral.

Tools have teleology. They have an intended purpose. They are pointed toward a particular vision of the future. If there is anything we should learn from the past few decades with small glowing rectangles in our pockets and algorithmic newsfeeds on our screens, it should be that technology forms or deforms us toward particular ends.

One of my heroes, the Canadian physicist, philosopher of technology, activist, and educator Ursula Franklin reminds us of this when she says:

Start also by considering not only what a specific new technology does but also what that technology prevents. Because of that technology, what can no longer be done? Whether it’s road and railway, fax and postal system, computer learning versus other ways of learning, or CD versus book, one has to look both at the enabling and at the foreclosing angle of any way in which things are done. When teaching through new technologies we must highlight not only the skills the new devices bring but also the skills that are not developed because of the use of those devices. It’s often a very real trade-off. The advantages of the new technologies don’t come for free, and the cost is not only in money.

Ursula Franklin in "Using Technology as if People Matter"

Wise words for us in 2025 as we grapple with the role that artificial intelligence should play in our society and world. To put a more visual point on it, consider this 2x2 diagram that you'll find posted outside my office on the second floor of Parsons. It is adapted from a talk my friend

gave a few years ago, titled "The Innovation Bargain." What he articulates is very much the same idea that Franklin is getting at. When we think of technology, we often think only of its enabling aspects. But technology is always simultaneously enabling and disabling.Whenever we eliminate a certain burden, we simultaneously remove the potential for doing something you previously could do. Consider, for example, the many ways that smartphones are a required tool to function in modern society. There is a growing set of things that cannot be done without a smartphone. But even more sinister is the fourth quadrant. This represents the new things we are compelled to do. The new tool so shapes our world that we must live in a certain way.

Our shared endeavor

At the end of the day, the core mission of Harvey Mudd College is not to be a place where you get an excellent technical education that sets you on a trajectory to land a good job, be a thoughtful and engaged citizen, or even to set you up to provide for your family and loved ones. Of course, all of us want those things for each other, because they are meaningful parts of a flourishing life.

But those things are means, not ends. Our true end, I would argue, is to live into the fullness of what we are as humans. There is a true diversity of thought about what exactly that is. Aristotle argues for the pursuit of eudaimonia, or human flourishing. Nietzsche rejects the idea of a fixed telos altogether. Transhumanists argue that technology should be used to help us overcome our limitations to optimize our biology and enhance our cognitive capacity. As a Christian, I believe my purpose is to follow Jesus’s call to love God with all my heart, mind, body, and soul and to love my neighbor as myself.

These questions about purpose are big enough that each of us will almost certainly come to different conclusions. That’s ok. But what matters most is that we are asking the same questions. Questions like:

What does it mean to be human?

What does a good life look like?

Who am I and why am I here?

These questions don't have easy answers. They are the types of questions that will require us to engage in a life-long dialectic journey of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis as we iteratively work to get closer and closer to the truth. But what you have in these next few years, at this place, is the chance to do that in a community of like-minded individuals who are similarly motivated to understand what a better future is and how we can get there.

You see, the mission of this place is to cultivate humans. It's to equip you not just with the technical knowledge to solve differential equations, but to understand what their solutions are useful for. It's to help you know not just to know how to solve technical problems, but to understand what questions those solutions are addressing and how they fall short of a full solution. It's to help you understand the societal and historical context within which your work exists, and how that shapes the way you think about your work.

Back to the Future

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua - Māori Proverb

There is a proverb from the Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, that has been shaping my imagination in recent days. The proverb, when translated, means "I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past."

When I read the Harvey Mudd mission statement, this image resonates with me. It is a reminder that as we seek to be part of making a better future, we must keep in mind that we walk backward into it. This, I think, is what the founders of this place were encouraging us to do and what I hope we continue to do as we move forward.

Leading into the future must be shaped by practical wisdom: the cultivation of curiosity and critical thinking; compassion, courage, integrity, and humility; citizenship and neighborliness; confidence, perseverance, and teamwork.

As we consider what it means for us to be part of building a better future, let us never forget that we move into the future with our backs toward it. With that in mind, we would be wise to move with caution, constantly reminded that there is much we cannot see.

Got a thought? Leave a comment below.

The Book Nook

Kicking off sabattical with a little lighter reading. Gotta love some John Grisham. Enjoying it so far.

The Professor Is In

In a few weeks, on September 10 @ 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm EDT, I’ll be giving a guest talk on Zoom for the MIT Teaching + Learning Lab. I’ve titled my talk “Cultivating a Convivial Classroom in the Age of AI” and will use this container as an opportunity to synthesize many of the ideas and thinkers that I often wrestle with here on Substack. It’s open to the public, so I hope you’ll register to attend if you’re available!

Leisure Line

We had a fun family beach day at Huntington Beach last Friday. The weather was perfect, and I even happened upon a sand dollar in the ocean.

Still Life

Yesterday’s excitement was this not-so-little guy who decided to (somehow) make his way inside our house. Not exactly Mrs. Brake’s idea of a good time, but I managed to catch him and relocate him back outside where he belongs. Index finger for scale in the second photo.

I am so glad my son was educated at HMC by people like you.

Great talk, Josh! I love the Innovation Bargain diagram, too! Very much in line with what I've read and heard from Andy Crouch. Excellent reflections, thanks!