Welcome everyone to the latest edition of my favorite game of 2024: “Utopia or Dystopia, You Decide!”

Last week this tweet from Sam Altman went viral. I mean, at one level I get it. From a purely technological specifications perspective, I can understand and appreciate his point. 100 billion words says something not only about the scale of OpenAI’s computational resources but also about how widely their tools have been adopted and incorporated into our lives, just a little over a year since ChatGPT was released to the public.

But the numbers just hide the real point—the story behind these numbers and the comparison. That story determines whether Sam’s tweet instills excitement or terror.

How you respond to that story says a lot about your vision of the good life. The answer is obvious to Sam.

Not sure exactly who the “you” is here but it probably at least includes

, , and . I’d be happy to be in their company. Sure, some of what we are writing could be (mis)construed as writing “about why we are going to fail.” But that misses the forest for the trees.We’re writing to ask the legitimate question: is your definition of success and “securing our collective future” actually something that is aligned with human flourishing?

As much as generative AI can help us be more productive, efficient, and perhaps even creative in certain situations, efficiency and productivity are not fundamental human values. Efficiency is only worth pursuing to the degree that it helps humanity to flourish.

This is not a question that science and technology can answer. The implicit inclination in the mind of an engineer is to make it cheaper, faster, and better. But these metrics miss the larger point of what the whole thing is for in the first place. This is where we would do well to remember the wisdom of philosophical and religious pursuits of knowledge.

It’s no use doing something faster if it’s not worth doing at all. While some fraction of those 100 billion words might help us, I’m suspicious that many more of them are simply adding to the noise.

We’re already drowning in words. We shouldn’t continue adding to the noise and thinking that things will be ok. At the risk of missing the forest for the trees myself and reading too deeply into a few tweets, today I’d like to probe a bit underneath Altman’s tweets to try and uncover the sorts of questions and critical lenses we should be taking towards these kinds of statements.

Apples to Oranges: All Words Are Not Created Equal

I talk to my students all the time about the importance of units. In an engineering context, a number without units isn’t worth anything. If you want to compare two quantities, you’ve got to make sure they’ve got the same units.

This is the first issue with Altman’s comparison: his units are not equivalent, even if they might appear to be at first. While humans and machines can both generate words, the process that generates those words matters. For an LLM like ChatGPT or Gemini, that process is an algorithm, taking a given input (the prompt) and computing an output using a complicated computational architecture that has been trained on a large corpus of text. The output of this computation might be words, but these words are not the same as those generated by humans.

The words that we humans generate are inspired by thought. Writing is thinking. Words express ideas. Language imposes limitations on our ideas and constrains our ability to express them, but behind the words we write or speak is an intention and a particular thought that we are trying to communicate.

While at a surface level, we can compare the amount of machine-generated to human-generated text, that comparison is ultimately not very meaningful. One is the result of a conscious, embodied creature. The other is the output of a machine, however sophisticated. The distinction matters.

The Metric Matters: Search for Signal

Even if we ignore the fundamental difference between machine- and creature-generated words, this doesn’t mean that machine-generated words are altogether worthless.

Altman’s celebration here is of a superpower: words with no effort. Anyone who has written for any amount of time knows how difficult it is to write and write well. The source of the original quote is a bit sketchy, but regardless it’s golden: “Writing is easy. You just open a vein and bleed.”

What our world needs is not more for the sake of more. This is the fundamental idolatry of our modern age, powered by our technology-saturated society and our techno-optimism: more energy, more food, more years, more, more, more. When will we realize that more is literally going to kill us?

The celebration of more words in less time is deeply ironic. It’s hard for me to think of many things that our world could use less than millions of machine-generated words. Matthew Kirschbaum’s article in The Atlantic about the coming Textpocalypse makes this point well.

I’m not arguing that there are no effective and good uses for LLMs. I think there are. For example, LLMs can be very helpful for writing computer code. In many programming languages, there are strict syntax requirements and standard ways of writing code. Creativity for the sake of novelty in these contexts is often a liability, not a strength. In this context, I can see the advantage of having an LLM programming partner that can act in effect as a sophisticated autocomplete engine. This type of application is narrow and that’s a good thing. The more specialized a tool is, the more easily it can be understood and appropriately managed.

However, I continue to be very pessimistic about the impact of LLMs on our ability to write more generally. Writing, like almost anything worth doing, is a process of which struggle is a critical part. The dream of a machine that somehow reads our thoughts or captures them in a prompt of some kind just doesn’t work—the whole point is that writing is a process—when you start writing, you don’t know what you think! This short article from

makes this point clearlyI think it's far more important to write well than most people realize. Writing doesn't just communicate ideas; it generates them. If you're bad at writing and don't like to do it, you'll miss out on most of the ideas writing would have generated.

This is, in essence, the motto for why I write this Substack each week. I have no grand plan for what I’m going to write about. After I schedule one post to go out every Monday night, it’s back to the drawing board to try to tap into what’s resonating with me for the next week.

As I’ve written before, it’s important to fall in love with the process instead of focusing too intently on the product. It’s not to say that Sam’s “grind to secure our collective future” isn’t worthwhile. I just think grinding to secure our collective future looks a lot more like writing Substack posts than he thinks.

Authenticity Matters

I for one am not interested in reading prose generated by OpenAI’s machine. When I read, I am looking to connect with a creature. I want to get in a writer’s head, to see the world through their eyes, and to challenge my own perspective. What I want for my students is not primarily the product of a good piece of writing, it’s the development of the process of being able to think well and express that thinking through the written word.

I won’t go so far as to say that machines have no place in the writing process. I believe that LLMs, like word processors, spell check, and peer review can offer some benefits for helping us to write more effectively. I appreciate how

and others like have been on the vanguard exploring this area. But machines will only help us write to the degree that they help us think more clearly.As I was working on this essay over the weekend I was reminded of an old song from one of my favorite bands, Switchfoot. Their song, “Adding to the Noise” feels like it has something to say to us here.

What's it gonna take to slow us down

To let the silence spin us around?

What's it gonna take to drop this town?

We've been spinning at the speed of sound

Stepping out of those convenience stores

What could we we want but more, more, more?

From the third world to the corporate core

We are the symphony of modern humanity, yeah

If we're adding to the noise

Turn off this song

If we're adding to the noise

Turn off your stereo, radio, video

Finally, in case we have forgotten, speaking the most words is not a competition we should strive to win.

When words are many, transgression is not lacking, but whoever restrains his lips is prudent." – Proverbs 10:19

Got a comment? I’d love to hear it. Shoot me an email or leave a comment below.

The Book Nook

I’m still not quite finished with Unreasonable Hospitality by Will Guidara, but it’s continuing to be an excellent read. It’s a good reminder about the importance of reading thoughtful professionals in fields that might seem far from your own. As an educator, I’ve been amazed to see the connections that translate from Will’s experience in the restaurant world to the challenges and opportunities of my word.

Without exception, no matter what you do, you can make a difference in someone’s life. You must be able to name for yourself why your work matters. And if you’re a leader, you need to encourage everyone on your team to do the same.

The Professor Is In

This year for E80 we moved our course materials system from a Google Sites website to a Quarto site hosted on Github Pages. This has been fantastic for many reasons:

It allows us to easily track changes as we make updates to the material. Almost all of the course materials are checked into source control, which means we can easily maintain the revision history for all our course files. This also enables you to easily see the change log in the commit history of the repo.

It enables effective collaboration. Branching enables us to easily separate our development from the live site and to update the site only once we’re at a point where the changes are stable. Furthermore, having the git backend allows us to see not only what files have changed, but what specific content within them has changed. This is very valuable and much easier than trying to watch revisions on MS Office docs or Google Docs.

Quarto’s support of GitHub Actions allows us to have a continuous integration pipeline where the website is automatically re-rendered whenever there is a new commit to the main branch. This is a bit of a small perk since it’s not much more complicated to render locally and publish directly from there, but it is convenient.

I’ve thought about making a short video on this sometime, but it hasn’t happened yet. If you’d be interested in learning more about this, click here to send me a short email to let me know!

Leisure Line

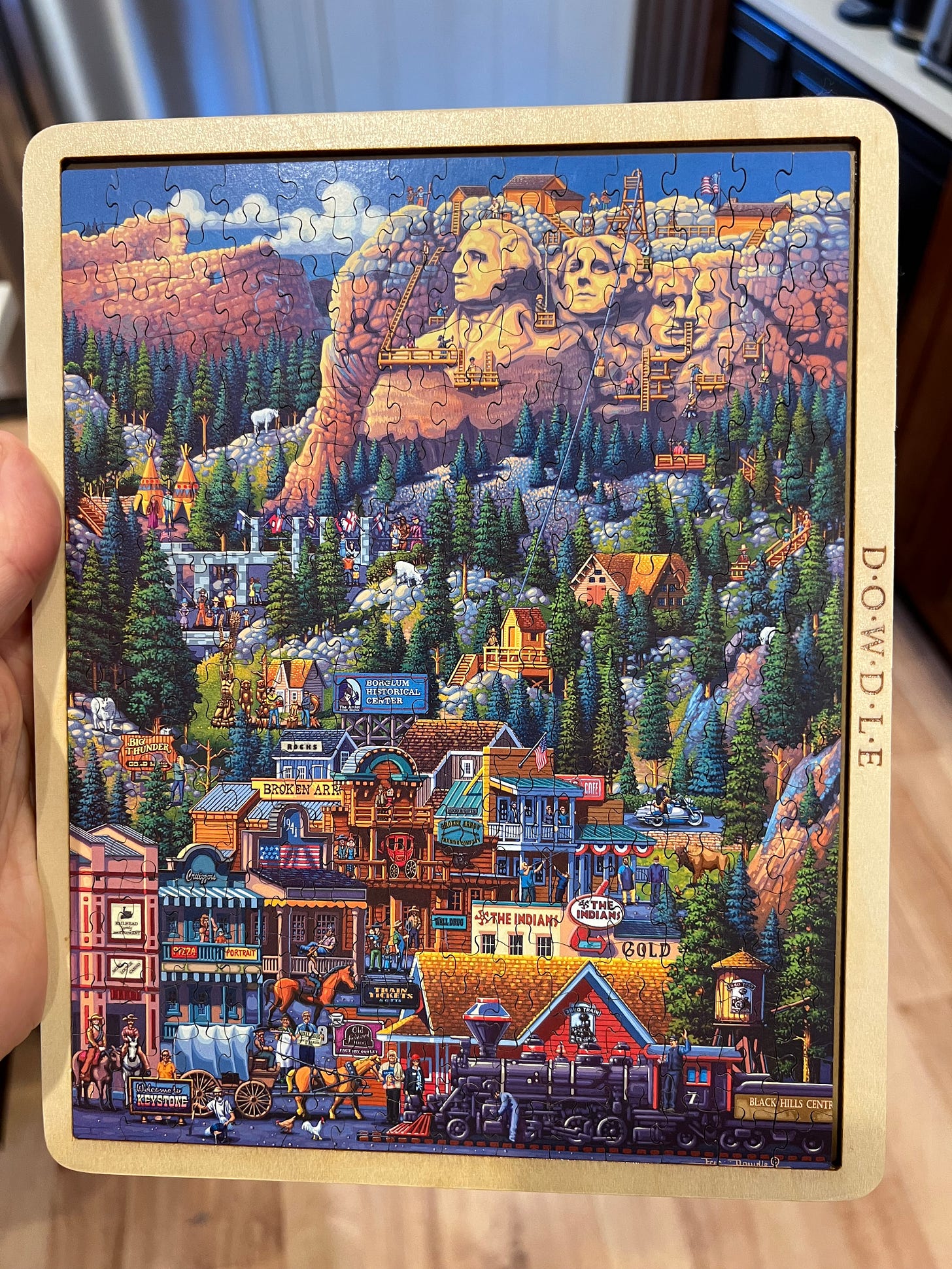

Finished this 250-piece mini puzzle last week with some friends. This is one of four from a National Park pack I got from Costco a few months ago. Super fun!

Still Life

It’s a little hard to tell, but that bucket is full up to just below the top of the square of the Home Depot logo. It was empty before the storms started.

“However, I continue to be very pessimistic about the impact of LLMs on our ability to write more generally. Writing, like almost anything worth doing, is a process of which struggle is a critical part.”

100%.

This is true of all art, too. I watch as the LLM companies move into artistic spaces (see the Sora announcement from last week), and I become more enraged. These are de facto desacralized applications to a sacred expression. In 2 decades, we’re going to ask what it means to be human, and a whole generation will shrug their shoulders, type the question into a chatbot, and receive an AI-generated documentary (with killer A and B roll) giving a very non-human answer. I’m no futurist, but you don’t have to be one. In the words of Dylan, “you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

I'm actually writing to ask "Can your definition of success and 'securing our collective future' [eve] actually [be] something that is aligned with human flourishing?" I'm not terribly concerned with whether it is or not because I think history shows us that, to date, much of the large-scale development done by robber barons like Altman is inherently inimical to human flourishing. Sure, the large corporations that are these men's legacies donate to society, building libraries, hospitals, universities, museums, etc. But their donations are a by-product of their robber-barony, not its central focus. Had they pursued the missions to which they donate with all the vigor with which they pursued their various industries, the world would have been a much different and far better place.

Thanks for this, Josh. Your writing brought me clarity on my own. We need to ask these questions loudly and publicly.