When Efficiency Is Worthless

What matters most is where you're going to spend the margin

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available without a paywall. If my writing is valuable to you, please share it with a friend or support me with a paid subscription.

Just because a new technology allows you to do something faster and better doesn’t necessarily mean that technology is good for you. In fact, sometimes it makes things worse.

The question is not just about what a technology enables us to do more efficiently, but about how it makes those gains happen. Not only that, but we often assume that whatever time, money, or energy we get back from doing a task more efficiently is automatically spent in a more valuable way. This is not always the case. If we get our chores done faster but use the time we save to sit and scroll our social media feeds or answer more emails, is that really a net win in the grand scheme of our flourishing?

We need to keep this tension in clear view as we run the efficiency calculus on all the new AI tools that promise to save us time and enable us to eliminate drudgery from our day-to-day work. (As an aside, personal experience and the anecdotes of friends suggest that many things that AI promises to make faster are actually more frustrating and take longer in the end.)

On grading and AI

To be sure, there are tasks that no one enjoys doing and are truly worth doing only because they need to get done. These kinds of tasks seem to contribute little to a flourishing life. But there are plenty of tasks that require significant effort from us that are still worth doing, even if a new tool can promise to do them for us more efficiently. Sometimes that’s true even if the new tool can do it better when judged by some metrics.

I’ve been thinking about this recently after reading Marc Watkins’ piece from last week. In it, he articulates the dangers of using AI to grade and give feedback on student work. This matters because it is one of the most popular examples of AI being marketed to educators.

It’s understandable that this is the target of so many ed-tech startups. I have yet to meet an educator who enjoys grading for its own sake. As the saying goes, “I teach for free. They pay me to grade.” If you start to have conversations with educators, grading will come up as one of the most dreaded activities. It is one of the tasks for teachers that often feels like the most effort for the least payoff. It takes a lot of time to give good, deeply considered feedback. To make matters worse, it often feels like that effort goes largely unseen and unappreciated by students who just look at the number at the top of the page and then move on, rarely taking the time to review the feedback or reflect on how to learn and grow from it.

This problem, like most problems in education, has enough blame to go around on both sides. The frustration of educators that their feedback goes unread may be well-justified, but oftentimes the students also have valid reasons for not paying attention to the feedback. For one, we often fail to give students an incentive to read and incorporate the feedback. Expecting that our students will read the feedback to synthesize some high-level takeaways and identify gaps in their understanding often ends up feeling like we’re asking them to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. Especially if we don’t explicitly scaffold assignments so that it is clear to our students that we value their ability to reflect and grow from feedback, it’s no surprise that they don’t pay attention. This is often, at least in part, a failure in the design of the course.

It’s not a walk in the park for educators either. Giving effective feedback on student work requires not just reading a single piece of a student’s work and assessing it according to a rubric. The most effective feedback is given by one human who deeply knows another. It’s given by a teacher who sees a student not just as the summary of the work that they’ve produced in a particular class, but understands the trajectory of growth that they are on. This kind of feedback is deeply human, aware of the things that students are struggling with, both inside and outside of the classroom. It’s the kind of thing that doesn’t and shouldn’t scale.

But for many teachers, especially at the primary and secondary levels, there is a significant pressure to prepare students to perform well on a specific summative assessment like year-end standardized tests or AP exams. At their best, these exams are a tool that can be used to assess a student’s ability. But in a system with so many competing pressures, it’s easy for a single data point to carry an evaluative weight that goes far beyond what it should.

Automation temptations

This is the world in which the AI grading cookies enter. Tempting, huh? Why not use a tool to more quickly give feedback on student work? At the end of the day, it’s because AI grading is a reasonable answer to the wrong question.

As I’ve been saying one way or another for several years now, the silver lining of the pressure that AI is putting on education is that it gives us the best opportunity we’ve had in years to put our foot in the ground and move in a different direction. The path of AI grading exemplifies what I like to call the more efficient path to nowhere. Figuring out ways to do things that should not be done ever more efficiently is not worth doing.

Streamlined learning management systems, automated grading, faster lesson plan generation—none of these ideas is bad on their face. But these “solutions” fall into the same exact trap we’re trying to save our students from.

If we only care about the essay checking a set of boxes around grammar, syntax, length, and style, then who cares whether students use an LLM to generate it? If all that matters is the product, then more efficient means are welcome.

But that is not the way through this moment. The way forward is to reconnect to our foundations and rethink everything we are doing in light of AI. Not because we should infuse AI into all the things or even because we should change anything. Sometimes, the best answer is just to re-justify what we are already doing. But regardless of what we do, we need to teach with an awareness of the ways that AI is putting pressure on students and educators alike. We need to revisit what we are doing so that we can justify it in the face of students, colleagues, and administrators who will ask us “why not?” when they see the marketing reels for the latest and greatest whiz-bang AI tools.

Often enough, the answer will be that the more efficient way is not worth taking because making it more efficient will sacrifice the essence of the thing itself.

In the face of the coming AI grading apocalypse, we must reject the temptation to try and patch up the existing system with duct tape. We should do some demolition work instead.

Instead of using AI to grade, do this

I’m certainly not suggesting that rethinking our work in light of AI is easy work, just that it is better than the alternative of giving up and giving our work over to tools that are powered under the hood by sophisticated autocomplete. We’ve fallen into the trap of the sunk cost fallacy for too long, thinking that the only way forward is to patch what we’ve got rather than make a move to reset and restart. All AI does is open our eyes to the ultimate end of the game we’re playing. It’s not a place we want to go.

Instead of going down the route of AI-automated or assisted grading, a much better way is to take the moment to rethink our entire system of grading as a whole. This is what I’ve been doing for the past few years, revamping my courses to use specifications grading instead of a traditional grading scheme. I’ve also spent a lot of time focusing my efforts on giving students opportunities to resubmit their work when it doesn’t meet standards the first time around and helping them to show their work rather than simply come out of my classes feeling like their letter grade is the best indication of their work. I’m convinced that these threads will play a significant role in reshaping our educational institutions for a world saturated with generative AI.

The best news for educators in all of this is that we don’t need to start from scratch. There is a small but active and growing group of faculty who have been championing ideas under the umbrella of alternative grading that can give us a set of building blocks to rapidly rebuild better systems and structures in our own context.

This is exactly the kind of path that can help us to pivot from the slippery slope which ends with students using AI to generate their work only to be graded by the teacher’s AI with, in the words of Susan Blum a few weeks ago, “no humans being changed in the process.” (My only quibble with this statement is that humans are indeed changed in this process, just in a way that makes them ever more machine-like and stripped of their agency).

If you want to pique your interest in alternative grading, there is no better place to start than Robert Talbert and David Clark’s Book Grading For Growth and their Substack by the same name. Linda Nilson’s book Specifications Grading (newly released second edition hot off the presses!) was also very valuable in my own journey to revamp my courses. Start by reading just a few of the things that Robert and David have shared over the years, and I think you’ll quickly find your curiosity piqued and your imagination stimulated.

Grading is just one example, but it’s a big one right now in education. Educators must be up to the task to justify why we are spending our time to invest in things that look, at least on the surface, to be easily automated by technology. If we don’t, we’ll need to live with an ever-increasing risk that the deeply human things we do in education will be redefined as menial tasks as technology creates ways of easily creating the product without the process.

At least we’re in the same boat as our students. Let’s work together to keep it afloat for all of us.

Got a thought? Leave a comment below.

Reading Recommendations

Love Daniel Goodwin’s latest “On Seriousness”.

Embracing seriousness means shifting the elite student’s dream job from well-manicured analyst to hands-on, risk-tolerant industrialist. It means popping the balloon of vague prestige, ignoring the student protest du jour and celebrating those who get into the dirt and dig for gold themselves. It means appreciating that farmers are actually very smart, expert machinists are in high demand for a reason, great inventors/scientists are not a commodity and that those in the physical defense roles (military and police) are worthy of your gratitude. It means active measures to make all children healthier and fearlessly increasing standards to compete on any field. We must identify and appreciate seriousness while jettisoning our patience with unserious or anti-serious behavior.

In case you missed the link earlier, you should definitely go read Marc Watkins’ recent post on AI grading.

Derek Thompson, insightful as usual, on why everything is television.

[p]erhaps, this is a good place for a confession. I like television. I follow some spectacular YouTube channels. I am not on Instagram or TikTok, but most of the people I know and love are on one or both. My beef is not with the entire medium of moving images. My concern is what happens when the grammar of television rather suddenly conquers the entire media landscape.

The Book Nook

I’ve been hearing about Iain McGilchrist’s book The Master and His Emissary from a number of my friends, and nearly all of them talk about the way that McGilchrist’s writing has shaped their worldview. I’m excited to dig in.

The Professor Is In

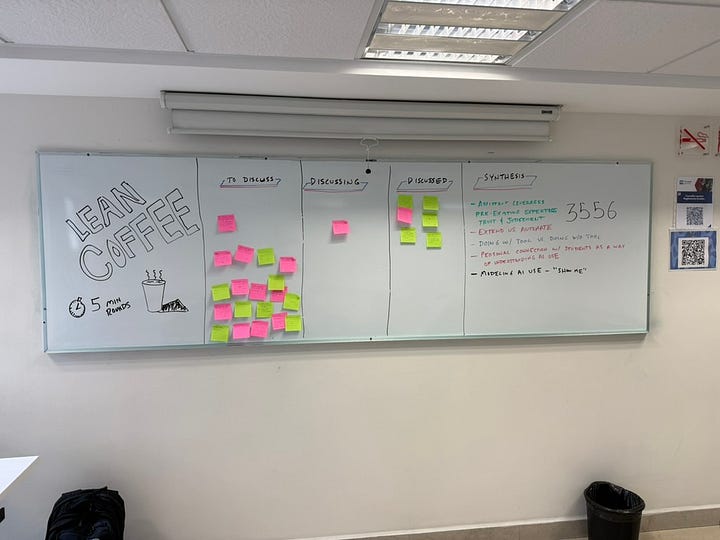

Had a great time last Friday speaking in Mexico City at The Anglo Professional Educational Conference. Grateful for the organizer’s invitation and the chance to connect with a variety of Mexican educators and school administrators about AI and education.

Leisure Line

Had a great time last week taking the whole family to have a late picnic dinner while watching the Claremont-Mudd-Scripps (CMS) Men’s soccer team play Caltech.

Still Life

Found this guy outside this week. He really wanted to attack my phone!

I must be one of those rare crazy professors who loves grading student papers. The thought that anyone would even consider offloading such important work to an A.I. is appalling to me. Yes, assessing student work and providing clear, useful, thoughtful feedback on drafts and final versions of essays takes a lot of time, but that's part of what I got paid to do for 25 years as a philosophy professor.

Thanks for this deeply thoughtful piece, Josh. And it's a great reminder to me to keep rethinking (and rethinking and rethinking) my own grading practices. Appreciate your work.