Bull, Cow, and Writing Robots

The problems around AI-generated text aren't new ones—they are fundamental to what it means to know something and communicate it

Effective writing relies on facts and the connections between them.

Absent either one, an essay will suffer. The tension between these two aspects has always been a part of clear writing but is even more important in the world of generative AI.

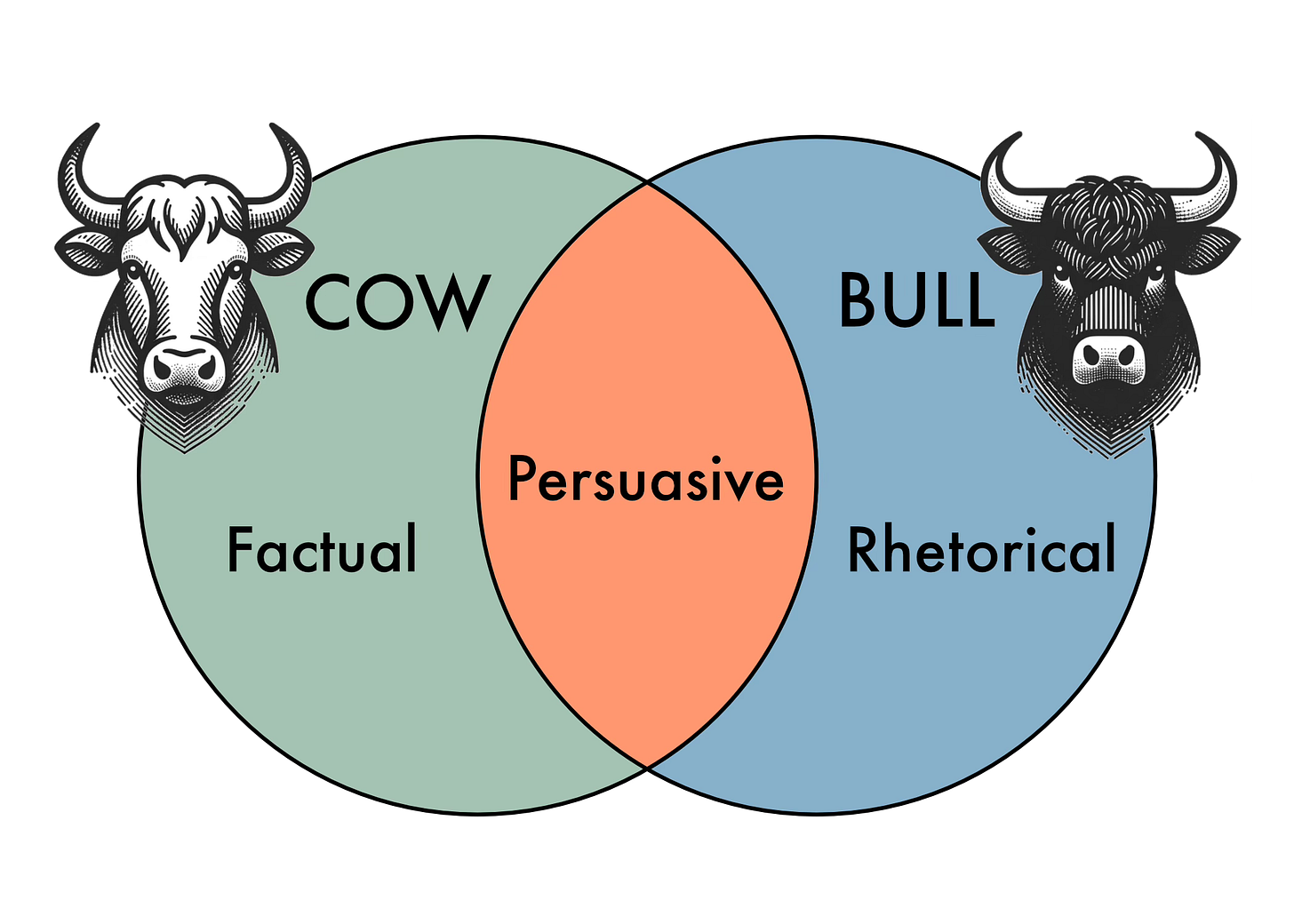

Today I want to share an essay I learned about in high school that has shaped the way I think about writing ever since. It’s about bull and cow. Here’s a map of where we’re going:

Good writing needs both cow and bull.

The categories of bull and cow help to explain some of the issues that generative AI is exposing in the way we interact with writing. These issues aren’t new, but generative AI is giving us a clearer view of them.

Understanding bull and cow can help us to write better and stand out in a world that is already drowning in AI-generated text.

Bull and Cow

My first introduction to the concept of bull and cow was in one of my high school English classes with Mr. Bair. I’ve written before about Mr. Bair1 and the influence he had on me. Many of my students have heard me tell them that their ability to communicate will be the most important skill they learn—I can’t tell you how thankful I am to have heard this from Mr. Bair as a sophomore in high school. It’s hard for me to think of a piece of advice that’s been more valuable to me in my career thus far.

The story of bull and cow comes from an essay written by William G. Perry, a well-known educational psychologist who taught at Harvard in the mid-1900s. In his essay “Examsmanship and the Liberal Arts” Perry tells the story of a student, pseudonymously named Mr. Metzger. It’s worth your time to read through the whole essay, but here’s the summary.

The story begins with our main man Mr. Metzger searching for a rehearsal for a play he is in. He peers into the theater. Seeing no one, he assumes that he has missed a memo and that rehearsal was canceled. He leaves.

On his way out, he runs into a friend going to the classroom next door to take an exam. Curious, Metzger wanders in with his friend. Caught in the shuffle of exams being handed out, Metzger freezes and then finds himself with a blue book and a copy of the exam. This being the time before the internet and pocket-sized glowing rectangles, Metzger can think of nothing better to do with the time he was planning to spend at rehearsal. He writes “Geoge Smith” on the cover of the exam booklet and begins to write.

Unsurprisingly, Metzger does not do well on the multiple-choice section of the test. After all, he hadn’t done any of the assigned readings. He’s not in the class.

But his essay was a different story. Perry explains:

The essay question had offered a choice of two books, Margaret Mead's “And Keep Your Powder Dry” or Geoffrey Gorer's “The American People.” Metzger reported that having read neither of them, he had chosen the second “because the title gave me some notion as to what the book might be about.” On the test, two critical comments were offered on each book, one favorable, one unfavorable. The students were asked to “discuss.” Metzger conceded that he had played safe in throwing his lot with the more laudatory of the two comments, “but I did not forget to be balanced.”

When the dust settles, Metzger gets an A- on the essay. His friend, in good company with many of his comrades who are actually taking the class, receives a C+.

For the remainder of his essay, Dr. Perry explains why he believes Metzger deserves the A- even if his essay lacked grounding in specific facts. There are several lessons here to learn about effective writing:

The connections between the dots are as important as the dots themselves.

Don’t focus on the dots. Tell the story.

LLMs and generative AI tools offer us an opportunity to think about what really matters in writing, how we can pursue those goals as writers, and how we can revise our pedagogy to teach it more effectively to students.

To explain this I’ll leverage Dr. Perry’s bull/cow analogy.

To bull or not to bull

Perry’s defense of the importance of the narrative connecting the dots starts by defining two types of writing:

cow (pure): data, however relevant, without relevancies.

bull (pure): relevancies, however relevant, without data.

Most writing isn’t one or the other, but you probably can think of examples where an essay leans too far in one direction or the other. An essay that presents a lot of factual evidence without drawing the connections between it is heavy on cow. On the other hand, an essay like Metzger’s which paints the picture in broad strokes but without the necessary facts to help it stand strong is full bull.

Perry explains further:

To cow (v. intrans.) or the act of cowing:

To list data (or perform operations) without awareness of, or comment upon, the contexts, frames of reference, or points of observation which determine the origin, nature, and meaning of the data *(or procedures). To write on the assumption that “a fact is a fact.” To present evidence of hard work as a substitute for understanding, without any intent to deceive.

To bull (v. intrans.) or the act of bulling:

To discourse upon the contexts, frames of reference and points of observation which would determine the origin, nature, and meaning of data if one had any. To present evidence of an understanding of form in the hope that the reader may be deceived into supposing a familiarity with content.

Of course, any effective piece of writing will have a combination of both cowing and bulling, but Perry’s argument is that Metzger’s essay deserved the higher grade, even if absent the specifics.

If a liberal education should teach students “how to think,” not only in their own fields but in fields outside their, own - that is, to understand “how the other fellow orders knowledge,” then bulling, even in its purest form, expresses an important part of what a pluralist university holds dear, surely a more important part than the collecting of “facts that are facts” which schoolboys learn to do. Here then, good bull appears not as ignorance at all but as an aspect of knowledge. It is both relevant and “true.” In a university setting good bull is therefore of more value than “facts,” which, without a frame of reference, are not even “true” at all.

The facts are certainly important. But without the proper context and relevance, their impact is muted.

Add more bull

One of my favorite things to do as an academic is to find places to playfully break rules and contradict the status quo. Being even a little creative in the way that you communicate your technical work is one of the biggest opportunities to increase your SNR and make your work more effective.

I tried to do this throughout my PhD. It’s not always something big. A little pinch can go a long way. Here are a few examples.

1. Tell a story

A lot of technical writing is boring. Boring to write, boring to read, boring, boring, boring. This is the canonical example of too much cow and not enough bull. It’s a common failure mode for engineers like me. We are so taken by all the technical details that we miss the forest for the trees.

As I’ve written before, it’s important to think about the layers of your audience when you’re writing or speaking. And not just about their level of technical understanding but perhaps even more importantly, about their attention. Sure, there is a standard format and tone for technical writing but it’s not as rigid as you might think. Even just thinking about the length of your sentences. Keep some short. Then have a longer one to help hold the reader for a little longer and add some rhythm. Before you know it your text will begin to sing.

Whenever I write a technical paper or give a talk I try to pay close attention to the narrative and my story of discovery or development.

What sparked the idea?

How does it fit into the context of prior work?

How does it lay the groundwork for exciting future developments?

Not only does this connect better with your readers but it’s way more fun to write too.

2. Squint. Does it look yummy?

While not many people know it, my PhD advisor at Caltech enjoyed painting in his free time. This gave him helpful insight into designing effective and visually pleasing graphics for papers and presentations.

His goto line that we would all laugh about in the lab was the yummy test. To judge the color palette for a figure he’d tell us to squint and ask whether it looked yummy. While yumminess is subjective, there are a few good takeaways here: (1) squint to mix the elements together and get a sense for whether they go together well or clash and (2) pay attention to the aesthetic quality of your graphics.

This isn’t to say that you need to become an artist, but even a little bit of thought here on something as important as color can go a long way. If you know a graphic designer, talk to them!

And the next time you’re looking for a color palette, try out coolors. It’s a tool I’ve used for years now that allows you to quickly generate color palettes and try them out.

3. Be creative

The final idea I’ll mention here, which builds and expands on the previous two, is to take advantage of the opportunities you have to try out new ways of communicating your work. If you’re in a STEM discipline like physics or engineering it’s likely that you’re tied to at least some specific stylistic guidelines for the papers and talks that you give. But you might not be as tightly constrained as you think you are. It’s probably pretty similar to how Metzger’s friend thought he had to make sure to dump a lot of facts in his essay to prove that he “did the work.”

You already did the work. Tell the story.

One of the best ways to do this is to lean into your excitement and enthusiasm. If you’re truly passionate about something, it will come through if you let it. Even if you are somewhat constrained in a technical paper, you can create content online to share more broadly with the public and point them to the paper for more detail.

Every time you tell a story about your work is another opportunity to tweak it just a little bit and try out a new angle. Think like a comedian and always be workshopping your content to see what lands and reflect on why. By experimenting in this way you’ll learn not only what resonates with your readers and listeners but you’ll learn how to better tell the story yourself and uncover areas where you want to dig deeper.

Bull and Cow in the Age of Generative AI

Dr. Perry’s essay takes on new significance in our current conversations about the role of generative AI in the future of writing. On the one hand, you could argue that Metzger foreshadows AI-assisted writing. Just like Metzger, ChatGPT is good at connecting the dots between various words and sentences, but not necessarily in a way that makes any sense when you look closely. From this view, it looks like ChatGPT is full of quintessential bull.

But I don’t think this is right. If you look a bit more closely, the argument that Perry makes tells us something more profound: writing is about thinking. And thinking is about weaving together facts to tell a story.

The reason Perry argues that Metzger’s essay deserved a better score than those of his peers is that it actually contained thought. While he obviously was short on facts not having been in the class, he leveraged what he knew from other contexts to construct an argument.

If there is any one point we need to keep in mind as we begin thinking about how to engage with AI tools like large language models it is that writing is thinking.

If you outsource writing, you outsource your thinking too.

We need both cow and bull

As we approach a new world of writing, one where AI is embedded in ways both visible and invisible, Perry’s article and his description of cow and bull will continue to be relevant. We’re going to need both, as we always have, although in different ways and for different reasons.

We’ll need cow because as generative AI continues to take off, we’re going to see more and more misinformation and straight-up lies online. The truth will be increasingly more difficult to discern using the heuristics we’ve developed like looking at the source and evaluating credibility based on data like photo and video evidence. It’s already shockingly easy to create fake content that is indistinguishable from reality. We’re going to need to hone our senses for evaluating sources and pieces of evidence and continue to stay vigilant as generative AI technologies continue to improve.

But even as the facts are under attack and harder to nail down, we still need bull too. If we just decide to feed a prompt and some data into a generative AI tool like ChatGPT and then call it done I think we’ve lost the plot. LLMs are at their core very good at guessing correct syntax. Syntax and thought are two different things.

And yet, this doesn’t mean these tools are useless. I still think that generative AI tools like ChatGPT have the potential to be a significant aid in the brainstorming process. One thing that I have seen them do well is help to break me out of ruts in my thinking where I’m stuck and can’t see any new ways to connect the dots. In this light, they are just one more tool in a collection of tools to aid ideation and help us think more deeply.

Maybe ChatGPT or its cousins are nothing more than a mechanized version of our protagonist Mr. Metzger, weaving together the limited facts at its disposal to create a narrative that seems plausible.

That’s all well and good, but it’s not thinking. And if it’s not thinking it’s not writing.

Recommended Reading

Here are a few things I’ve read this last week that I think are worth your time as well:

in on his experience and reflections on creating a GPT version of himself using the new GPTs feature released by OpenAI at the end of last week. in on some of the implications of OpenAI’s new GPTs feature.A few pieces from the recent collection of essays “The Political Ideologies of Silicon Valley“ on Crooked Timber that are well worth your time.

Silicon Valley is the Church of Moore’s LawSilicon Valley Fairy DustBelief in the immutable nature of Moore’s Law is a matter of identity in Silicon Valley circles. But it is also a political project. Faith in Moore’s Law implies a distrust of government – government is too slow and cumbersome. Legislators and federal agencies cannot hope to keep pace with innovation, so we are better off demanding that they stay out of the way.

So I suppose it is unsurprising that, even as the pace of “internet time” seems to have stalled over the past decade or so, our tech titans and Silicon Valley evangelists have remained insistently committed to the idea of Moore’s Law.

Silicon Valley suggests that technology will cure social problems, but it exacerbates the social problems it claims its connectivity will cure. Facebook claims to be our cure for loneliness, but online, we became alone together, less able to find a common cause.

The Book Nook

As I mentioned in last week’s post, I’ve been digging into some readings on the philosophy of technology lately. In exploring some reading material I stumbled across this volume of compiled essays and excerpts edited by David M. Kaplan, Readings on the Philosophy of Technology. So far I’ve been enjoying it. These types of resources are really handy when you’re looking to get some exposure in a new field.

Here’s a list of what’s included:

Part I: Philosophical Perspectives

Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology

Hubert Dreyfus, Heidegger on Gaining a Free Relation to Technology

Herbert Marcuse, The New Forms of Control

Larry Hickman, John Dewey as a Philosopher of Technology

Albert Borgmann, Focal Things and Practices

Don Ihde, A Phenomenology of Technics

Philip Brey, Philosophy of Technology Meets Social Constructivism: A

Shopper’s GuideCorlann Gee Bush, Women and the Assessment of Technology: To Think, to Be;

to Unthink, to FreePeter Kroes, Design Methodology and the Nature of Technical Artifacts

Andrew Feenberg, Democratic Rationalization: Technology, Power, and

Freedom

Bruno Latour, A Collective of Humans and Nonhumans: Following Daedalus’s

Labyrinth

Part II: Technology and Ethics

Hans Jonas, Technology and Responsibility

Robert E. McGinn, Technology, Demography, and the Anachronism of Traditional Rights

Diane Michelfelder, Technological Ethics in a Different Voice

Tsjalling Swierstra and Arie Rip, NEST-ethics: Patterns of Moral

Argumentation About New and Emerging Science and TechnologyPeter-Paul Verbeek, Moralizing Technology: On the Morality of Technological Artifacts and Their Design

Part III: Technology and Politics

Langdon Winner, Do Artifacts Have Politics?

Michel Foucault, Panopticism

Richard E. Sclove, Strong Democracy and Technology

Jay Stanley and Barry Steinhardt, Bigger Monster, Weaker Chains: The Growth

of an American Surveillance SocietyLaurence H. Tribe, The Constitution in Cyberspace: Law and Liberty Beyond

the Electronic FrontierEvan Selinger, Technology Transfer and Globalization

Part IV: Technology and Human Nature

Nick Bostrom, The Transhumanist FAQ

Ray Kurzweil, Twenty-First Century Bodies

Hubert Dreyfus and Stuart Dreyfus, Why Computers May Never Think Like

PeopleEvan Selinger, Hubert Dreyfus, and Harry Collins, Interactional Expertise and Embodiment

Julian Savulescu, Genetic Interventions and the Ethics of Enhancement of

Human BeingsCarl Elliot, What’s Wrong with Enhancement Technology?

Part V: Technology and Nature

Erik Katz, The Big Lie: Human Restoration of Nature

Andrew Light, Ecological Restoration and the Culture of Nature: A Pragmatic Perspective

Strachan Donnelley, The Brave New World of Animal Biotechnology

Gary Comstock, Ethics and Genetically Modified Food

David M. Kaplan, What’s Wrong with Functional Foods?

Part VI: Technology and Science

Joseph Pitt, When Is an Image Not an Image?

Don Ihde, Scientific Visualism

Bruno Latour, Laboratories

Paul B. Thompson, Science Policy and Moral Purity: The Case of Animal Biotechnology

Sheila Jasanoff, Technologies of Humility: Citizen Participation in Governing

Science

The Professor Is In

These days campus is in the crunch time of the semester. Thanksgiving is just around the corner and end-of-term projects are really starting to ramp up. Time to buckle down as winter break is about a month away now. Hard to believe, but true!

Leisure Line

Had fun baking this cake for #1’s 4th birthday. Another rendition of the Funfetti Layer Cake from Sally’s Baking Addiction.

Still Life

Found this little guy in the backyard last week. He just chilled out on my hand for ten minutes or so. Pretty amazing little creature.

Likely to be forever Mr. Bair and never Jim to me.