Don't Tinker With AI In The Classroom

It's fine to play around by yourself, but if you choose to engage genAI with your students, make sure to think it all the way through

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available without a paywall. If my writing is valuable to you, please share it with a friend or support me with a paid subscription.

I'm away at the lake this week, but I'm starting to collect my thoughts for a few opportunities later this summer and fall to speak with K-12 school communities about education in the age of AI. At the end of the day, I want to help these groups build a 50,000-foot view of the situation. I don't want to offer narrow prescriptive solutions. I'd much rather offer frameworks and approaches that can equip teachers to leverage all of the wisdom and expertise they've built in their own contexts.

It's inevitable that teachers will be exposed to AI in their classrooms this fall, whether as a part of their own tools like Google Workspace, part of their learning management system, or directly through their students. These tools are being rolled out as on by default, often without even notifying teachers that it's coming.

The first thing to say is that teachers should feel the freedom to reject these tools outright in their classrooms. Even if AI is a potentially valuable tool in some contexts, the truth is that the expertise required to use AI effectively is often best built in the absence of AI assistance. Especially in elementary school, I'm unconvinced that generative AI should be a part of the curriculum. If anywhere, perhaps students should be exposed to it in the context of a computer class.

But if you do decide to dip your toe into the world of generative AI this fall, here is my suggestion. Don't tinker with it in your classroom.

The Dangers of Tinkering

I often have to explain to my sophomore engineering students the difference between experimenting and tinkering. Most of them, when they encounter a new problem, are naturally inclined to tinker, especially when they are under pressure. They look at all the variables in the problem and start to change things to see if it makes it better. What happens if I replace this chip? Maybe this resistor is bad? Perhaps if I unplug it and plug it back in? What if I just try this new thing and see if it fixes the issue?

The fundamental difference between tinkering and experimenting is the lack of a fully formed and researched plan. Tinkering is defined by an almost haphazard approach. It's risky.

Let me give you an example. Last week I was trying to run down a creak on my new bike. I had a hypothesis: a loose bottom bracket. I noticed that the sound seemed connected to when I was pedaling hard. So, I figured I would take off the bottom bracket, add some grease, and reinstall it.

After waiting a few days for a few new toys tools to arrive in the mail, I got to work. I figured I would address the non-crankset side first, since I wouldn't have to deal with the additional complexity of taking off the chainring. I grabbed my shiny new bottom bracket wrench and took off the cup on the non-crankset side. No problem. Added some grease to the threads and tightened it back up. Packed it up for the night and went to bed.

Imagine my dismay when I pulled the bike out for a ride the next afternoon and got the kids ready to hop on the back, only to be greeted by a red warning on the display: E44 Torque Sensor Error. Womp womp.

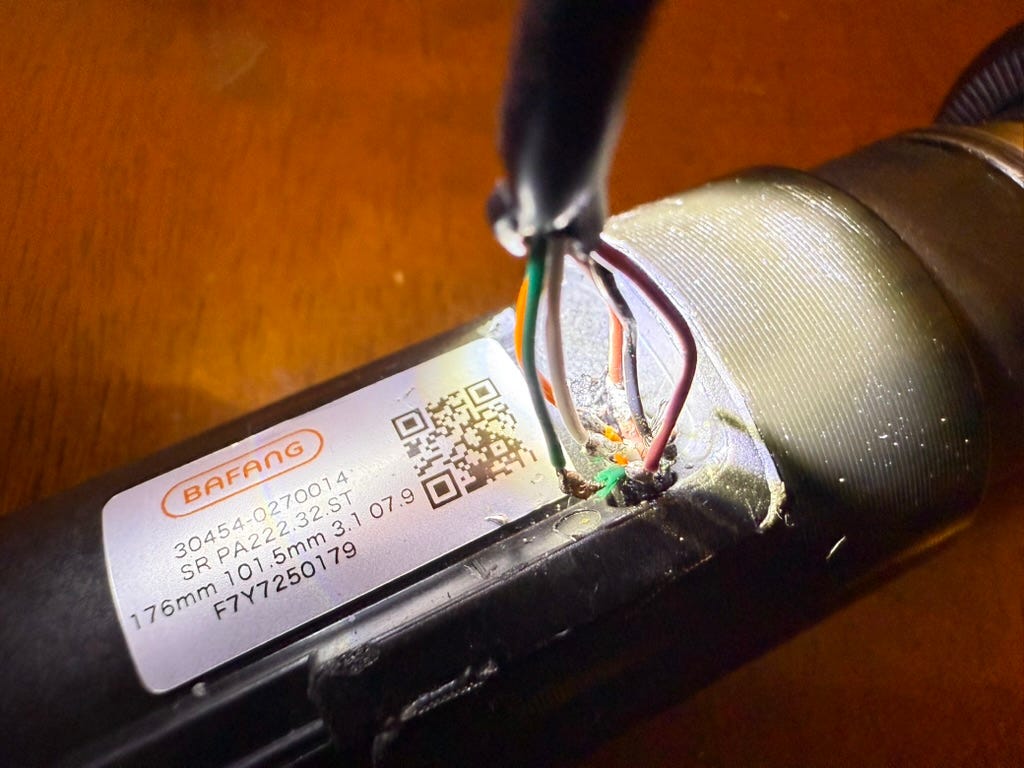

After doing some digging online, I figured out the issue. Turns out that the bottom bracket (which houses the torque sensor) is held fixed in the proper orientation by—you guessed it—the left bottom bracket cup. As I soon confirmed by removing the crankset and the right side of the bottom bracket, if you remove the left side first, you'll spin the bottom bracket cartridge along with the wires connecting the torque sensor to the control unit until you literally rip the cable in pieces. That's what tinkering gets you.

I've since been able to repair the sensor (quite miraculously, I must say) by painstakingly re-soldering each of the very small wires I tore inside the torque sensor cable to the small stubs of wire left exposed where it enters the torque sensor assembly that is part of the bottom bracket. This did the trick, combined with some of the three-year-old's pink nail polish to insulate the wires—gotta do whatcha gotta do). It works, but it was painful. All because I loosened the wrong side of the bottom bracket first.

The fundamental difference between tinkering and experimenting is in what happens before you take action. When you're tinkering, all you need is a hunch and some tools. An experiment, by contrast, has a step-by-step plan, an expected outcome, and a plan to assess whether or not the outcome has been met and what to do next if not. It's one thing to tinker when a potential failure will affect just you. It's a totally different ballgame when it impacts your students.

It's one thing to tinker with AI by yourself. It's not a bad way to start exploring these tools. But whatever you do, don't go live with the tinkering. You don't have to have it all figured out, but you've got to have a plan for both what you're going to do and how you're going to learn from the outcome, whatever it is.

Got a thought? Leave a comment below.

Reading Recommendations

This was a good piece from

highlighting Google’s recent rollout of Google’s Gemini for Education. I particularly appreciated the link to Jennie Dougherty’s piece about Google’s move to make these tools on by default.Let’s have more people over.

on how to embrace what she calls “Deep Casual Hosting.”The best way to tinker (and experiment) with AI is among community. In this post on

, lays out a blueprint on why and how to do it.The Book Nook

I’ve spent time with Jacques Ellul, Neil Postman, Marshall McLuhan, Ursula Franklin, but not much yet with Ivan Illich. This week I picked up Tools for Conviviality. In it, Illich unpacks what he means by the phrase that serves as the title of the book.

I choose the term “conviviality” to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment; and this in contrast with the conditioned response of persons to the demands made upon them by others, and by a man-made environment. I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value. I believe that, in any society, as conviviality is reduced below a certain level, no amount of industrial productivity can effectively satisfy the needs it creates among society’s members.

On the deformation of imagination.

Our imaginations have been industrially deformed to conceive only what can be molded into an engineered system of social habits that fit the logic of large-scale production. We have almost lost the ability to frame in fancy a world in which sound and shared reasoning sets limits to everybody’s power to interfere with anybody’s equal power to shape the world.

On whether our tools are serving us or the other way around.

For a hundred years we have tried to make machines work for men and to school men for life in their service. Now it turns out that machines do not “work” and that people cannot be schooled for a life at the service of machines. The hypothesis on which the experiment was built must now be discarded. The hypothesis was that machines can replace slaves. The evidence shows that, used for this purpose, machines enslave men. Neither a dictatorial proletariat nor a leisure mass can escape the dominion of constantly expanding industrial tools.

The Professor Is In

Last Friday, one of my summer students, Brock, hosted a workshop for summer research students at Mudd to build their own 3D-printed Microscopes. It was fun to see everyone building!

Leisure Line

Went out to brunch with my summer students last Friday at The Claremont Village Eatery. Super good food!

Still Life

I chuckled at this creative tip jar I spotted on family vacation and made a mental note to grab a few bucks from my wallet for the next time I visit.

Have to be honest -- my first thought is that if you had asked one of the AI apps for a diagnosis to begin with you would probably have avoided the problems that came with your tinkering. It was also interesting that when you got stuck you decided to do some "digging online". I would also suggest that supervised "tinkering" with AI is actually a good way for students to begin to figure out what it can do, what it can't do, as well as what it should do and should not do. We usually insist in class that they do what WE want them to do, solve the problems that WE want them to solve, and deprive them of finding out what THEY can do.

Great analogy.

Also good to see Illich! I find it odd that he's disappeared from so many conversations where his work is relevant.