I Grew Up Oblivious About Grades. It Ruined Me.

Now I’m on a mission to ruin you too

I didn't get a report card until high school. Growing up without grades ruined me because I can't help but see all the ways that grades detract from learning.

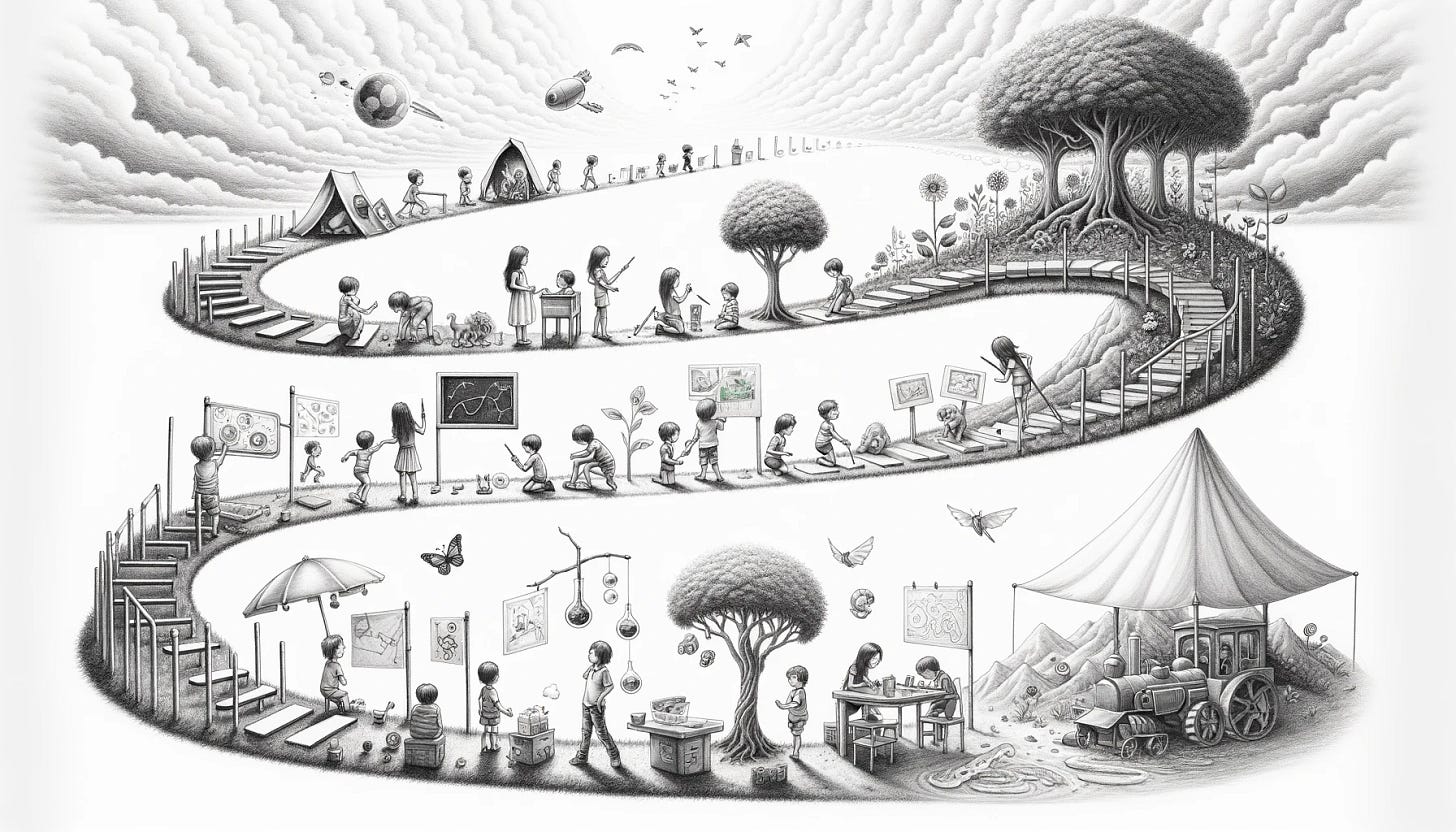

Grades themselves aren't the core of the issue, but they're certainly part of it. If we really want our educational system to be about learning, we've got to rethink how we're using grades. The lessons I learned from being homeschooled as a kid gave me a taste of what this might look like. It looks a lot more like gardening than cranking parts out in an assembly line.

The Absent-Minded Professor is a reader-supported guide to human flourishing in a technology-saturated world. The best way to support my work is by becoming a paid subscriber and sharing it with others.

Growing without grades

Most of what I remember about my elementary school days was a lot of reading and independently directed school work. Every year we would get a big delivery sometime in the summer with all the books and school materials for the year. I remember the excitement of seeing all the new school supplies and hauling the boxes into our bedroom to load the new books for the year onto the custom bookshelves Dad had built and suspended from the ceiling.

As August first rolled around we'd start hitting the books. Another benefit of homeschooling was being decoupled not only from the typical school day but from the school calendar as well. This meant we started in the dog days of summer and were done by Memorial Day each year. Each week my mom would take the curriculum for the week out of a big blue binder and put it in a clear plastic sleeve on the refrigerator so we could check off our work as we completed it. Each row was for a different subject or book: the math lesson and problems for the day, the chapters in our read-aloud, or as we got older, the pages we needed to read by ourselves in our assigned books.

We were known at the mall as the readers. Even though the stores didn't open until 10 am, the general mall building would open much earlier. Most weekdays you could find us there, doing laps around the mall with all the retired folks, listening while my mom read our read-aloud books to us as my brother and I walked. Once my little sister arrived, we took turns pushing her in the stroller. We were quite a sight.

One common caricature of homeschooling is that it's a wild west where anything goes. That may be true in some places, but not in my house. The absence of grades didn't mean the absence of assessment. In place of grades, Mom kept a pulse on our work and was able to sense how we were doing in a particular subject. To get an external assessment, at the end of the year, we would go for several days to take our appropriate version of the Stanford Achievement Test.

I don't remember asking about my scores. Even if I did, my mom had the wisdom to shield me from that information.

What would have happened had she told me reveals an important aspect of grades. The first thing I would have wanted to know was how I stacked up. I know this because it’s what happened when I did get grades in high school.

As a competitive person, once I left the confines of homeschooling for high school and college I was playing the game. I cared about my grades as a measure of my learning, but I was in it to win. I didn't just want to learn the material and do my best, I wanted to be the best. Sure, grades themselves give us some measure of our abilities to answer the questions correctly and to assess our learning. But that's often secondary to the comparative nature inherent in grades and test scores. What we often care most about is not how we do on some objective scale, but how well we do relative to others.

Thankfully the extrinsic motivation of grades didn't crush the love for learning that my homeschool years had cultivated, but it didn't help it flourish. My work at school was serving two masters: grades and learning. These masters, I learned, are often at odds with each other and cannot be simultaneously satisfied. I still loved learning, but the pressure to perform overshadowed it. I was good at the game, but the game wasn't good for me.

It wasn't until I got to grad school and recognized that grades were no longer going to be a primary measurement that I felt the pressure ease and the priority shift again to pursue learning without needing to optimize for a grade. I kept wondering: might there have been a better way to retain some of what I loved from my homeschooling years throughout my more traditional high school and college experiences?

It's about the story and grades are only a part

As I’ve embarked on my journey as a professor, I think a lot about those formative homeschooling years and wonder how I can bring parts of that experience into my classes. The core of the issue is to get clear on what we really want out of school and to thoughtfully consider how we create the environment for those goals to flourish.

Despite this tension between grades and learning, I do think there is a place for grades in some circumstances. For example, I was in many ways a beneficiary of standardized tests. They were able to validate, at least to some degree, what I had learned during my homeschool years. Having a common measurement across an entire population can help us, but we've got to get away from the idea that the goal is to be the best. Just like different plants require different amounts of sunlight, education is not one size fits all. We need to hold these two points in tension: that grades have many negative impacts when used as course feedback for learning, and yet, they can provide an imperfect metric which can validate some aspects of the skills and abilities that are a result of learning.

I'm not looking to throw out grades, but just to put them in context. I'm reminded of Kevin Kelly's exhortation: "don’t be the best, be the only." The problem with focusing solely on grades is that they are oriented toward competition. They naturally ask how you measure up to others instead of providing a data point about your strengths and weaknesses.

I think about this a lot when I'm reviewing the transcripts of students applying for research positions in my lab. As I look over the courses they've taken, I see only the tip of the iceberg: single letters which represent their entire body of work in particular classes. Gone is the nuance and complexity that is inevitably hidden beneath the surface.

If you are familiar with the broader landscape of higher education, you might be wondering whether I'm advocating for more colleges to adopt the types of alternative evaluation systems at places like Alverno College, New College of Florida, or The Evergreen State College. While each of these colleges has its own particular flavor of evaluation, they all jettison letter grades entirely in favor of alternative methods of evaluation like narratives written by students or faculty.

We need to encourage our students to reflect on their learning and about what their education is for. This type of exercise is valuable not only as a tool to help them think about the type of influence they might want to have on the world but to help them to understand their unique strengths and opportunities. But this doesn't necessarily mean that we must eliminate grades.

In this vein the "yes, and" approach of a place like Sarah Lawrence College (SLC) is worth serious consideration. Sarah Lawrence has three modes of evaluation:

Critical abilities assessments

In-depth narrative evaluations

Traditional grades

The critical abilities assessments allow faculty to assess students on six core competencies which include the ability to think analytically, to express ideas effectively through writing and speaking, to innovate, to work on a team, and to receive and act on criticism. The in-depth narrative evaluations are written by faculty members for their students to help them understand their strengths and areas for growth. It gives them an outside expert perspective on how they have grown during the class, what they have achieved, and where they might go next to continue to grow. These two additional forms of feedback add context to the student's grades to put them in context. They highlight the "only" aspect well.

This model in many ways mirrors what was so formative in my own story during my homeschool years. It wasn't that grades didn't exist, it was just that they weren't the primary mode of evaluation. When I was homeschooled, my mom was the prime evaluator, combining what she was able to assess in me and my siblings as we progressed through our schoolwork with external standardized evaluations each year that added additional data points to inform her assessment. She was able to evaluate us on the critical abilities or learning outcomes that are not captured by how we do on a test and to give us personal feedback and direction to help us understand our strengths and opportunities for growth.

Where do we go from here?

If we're going to reframe the unhealthy perspectives that traditional grading has on us, it's going to take a concerted effort from both faculty and students. Here are three things that will help to get the ball rolling.

1. Start with the learning objectives

As Stephen Covey famously wrote, "Begin with the end in mind." It can be very effective to think about where you want to end up and then work backward from there. The same approach can be very valuable when thinking about how you teach.

As we think about our courses or programs, our learning objectives need to be the guiding principles. These statements illustrate who we want our students to be and the types of things we want them to be able to do upon finishing our course or program. If you don't know what you want your program to do for your students, how can you decide how to make decisions about the curriculum or the contents of individual courses?

2. Foster storytelling

The ability to tell a story is a powerful way to contextualize grades. It’s one reason that many of these colleges include some narrative assessment alongside or in place of traditional grades. Grades are designed to be standardized and consistent across all our courses and students but that standardization is misleading.

As instructors, we need to put our curriculum in context and help students understand not only what they are there to learn, but why and how. Students also need to learn how to tell the story of their education. We can help them to do this by creating structure and space around storytelling in our courses and by giving students templates so that they can get a sense of how they might tell their stories.

3. Grade differently

If you’re a teacher, you’re likely in a scenario where you have at least some constraints around grades. It's unlikely that you could jettison grades entirely from your courses. But don't let that constrain your creativity.

While you may still have to assign an end-of-course grade, there are many different ways to arrive at that grade. I've written before about how alternative grading has become a significant part of my pedagogy in the last year. I used a version of specifications grading this past fall and also adopted it in some aspects of the course I'm teaching this semester. I find specifications grading to be well-aligned with what I am trying to do in the classroom as it is naturally suited to communicating high expectations for work while allowing students the ability to retry and revise work if it doesn't meet the expectations on the first attempt.

Beware Goodhart's Law

Our relationship with grades today often reminds me of Goodhart's law: "Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes." Put simply, once you start focusing on the measurement instead of the thing it's supposed to be measuring, your measurement becomes increasingly useless as an estimate of what you care about.

If we care about serving students well, we need to rethink grades. There may be no way to escape grades, but we need to do our best to link them to clear criteria and help students to understand how they are being formed by the work they are doing. This is what I appreciate about alternative grading techniques like specifications grading. Students still get a letter grade at the end of the day, but there is a clear explanation of how they arrived at that based on concrete descriptions of their work instead of a weighted combination of assignments graded from 0-100.

Growing up without grades ruined me in the best way possible. It helped me to build a foundation for a life full of learning and curiosity. I can only hope that I can do the same for my students.

The Book Nook

I’m still in the middle of The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles and really enjoying it. I particularly like how he weaves together multiple storylines from different characters. Been slow on my reading lately, but hoping to finish this one this week!

The Professor Is In

Spring Break was much needed, replenishing, and…over. Back to class today with the end of the semester already in sight as we quickly turn the corner into April. Looking forward to seeing the projects that all the folks in E80 are building.

Leisure Line

First PhD Pies, now Dr. Donut. Over Spring Break I decided I wanted to give homemade donuts a try. Folks, there is nothing quite like a warm donut coated in cinnamon sugar. These turned out amazing and were pretty simple.

Here’s the link to the recipe. Highly recommend!

Still Life

On Sunday afternoon we went to Descanso Gardens. The tulips are in bloom and beautiful. We also stumbled on a pretty cool rolly-polly bug which I just learned upon writing this are not actually bugs at all, but rather terrestrial crustaceans.

I grew up in a public school setting that encouraged the rat race of grades and rewarded all A’s students with gold cards that granted them all sorts of privileges, e.g. off-campus lunches, reduced ticket prices at the movie theater, ice cream socials, etc… It was an exclusive and rather toxic environment that was completely taken for granted.

I have since worked as a teacher at an independent K-12 school that in lieu of grades uses narrative assessment and a metric of 5 C’s (character, creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication) and I’ve been astounded at how effective this model can be in reducing the air of competition and helping students learn for learning’s sake. Particularly with the collaboration metric, we see students recognizing the value of others’ ideas and input in reaching a goal. I would love to see this method adopted more throughout schools, as it would undoubtedly help to curb the hyper-individualist mindset that keeps partitioning us off from one another.

Some late-night rambling and incomplete thoughts -

C- and D-students, and even B-students, haven’t experienced deeply, or even enough, of what success feels like.

Conversely, A-students are missing the innovative power of failing.

Is there anything more devastating than being labeled a [Letter-grade]-student? Even, or especially, in casual or overheard conversation?

Does effort need to equal identity?