The Optimal Number of Failures is Not Zero

Nobody likes failing, but a prototyping mindset helps to unlock the way to be intentional about iteratively turning small failures into success

Failure. Nobody likes it. We all do our best to avoid it. Unfortunately, there’s no way to succeed without it. You have to be okay with being bad at something before you can be good. But first, you’ve got to get to a place where your fear of failure doesn’t cripple you. A prototyping mindset can help.

Success through failure

The title of this article comes from the end of Josh Linkner’s interview with James Altucher that I listened to this week. In it, Josh and James talk about creativity and Josh shares some techniques that can help you be more creative. But what stuck out most to me was the part of the conversation where Josh and James talk about failure.

I’ve been thinking a lot about failure lately. It often comes to mind when I’m putting together a research proposal. This last week, I was working feverishly to put the finishing touches on a proposal that was due on Friday. Writing a proposal is always going out on a limb, stretching to reach something you can’t quite grasp. You’re taking a chance and pitching something. Even if the core of your idea is good there are so many places it could go wrong. You might fail along the way and these failures might ultimately add up to sink the whole project. So what do you do?

Failing comes first

When was the last time that you were good at something you tried right out of the gate? Even if you improve quickly, chances are that the first time you tried something it was not so far away from being a mess.

Earlier this year I embarked on a journey of rediscovering how to write in cursive1. Prompted in part because of the gift of a fountain pen last year, I wanted to experiment with writing in script. I started by tracing some pages of cursive letters. Boy was it a mess. You know that feeling of starting out on the right path and then all of a sudden you’re somehow turned around and have no idea how you got there? Yeah, my cursive lettering was pretty much like that.

Eventually, after a bunch of tracing pages filled with some…shall we say creative?…cursive letters, I finally took the dive and went all in and started writing my daily journal in cursive each night. My form still isn’t amazing, but what is amazing is the way that daily practice and some consistent reflection on the shape and form of the letters have helped me to get better. Now my script has gone from messy to barely legible, which, I think, means that my cursive has reached peak grandmother level.

The lessons of failure extend beyond my handwriting though. The first seven proposals I wrote as a new faculty member were rejected before I had my first one funded. I got rejected from half of the Ph.D. programs that I applied to. Stanford was even kind enough to send me their rejection on Valentine’s Day. How’s that for considerate! New activities I try in class rarely work the way that I think they will the first time around. And I’ve had plenty of misshapen pizzas and sticky doughs in my days making pizza (just ask my wife about the time I tried to sell the pizza to salvaged calzone move to save a particularly adventurous pie. Spoiler alert: it ended up in the trash).

Failure is a natural part of getting good. We don’t often celebrate failure, but I think we should. To be clear, I don’t mean that we should celebrate every failure. There are some failures that aren’t worth celebrating. Maybe we didn’t really put our heart into it and it failed because we just didn’t give it any care, attention, or effort. Those ones, I’m not so sure about. But the ones where we really do give it a concerted effort and try to put our best foot forward? Where we put ourselves out there and then learn from the feedback and flaws? Let’s celebrate those ones.

Learning to fail alongside my kids

So how do we learn to get more comfortable with failure? I think it has a lot to do with reframing our work as play.

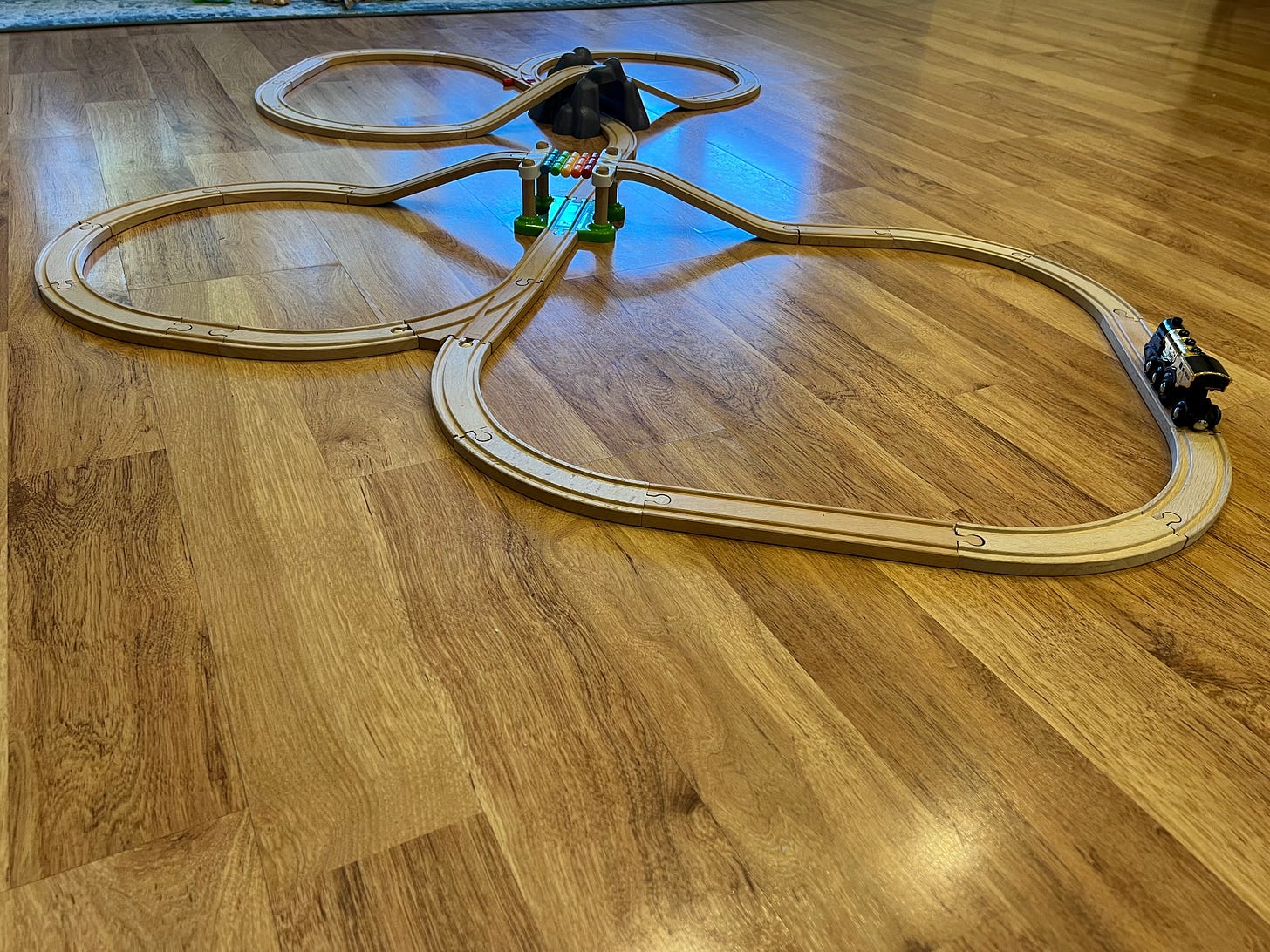

Recently my three-and-a-half-year-old has been really into Brio trains. When I’m playing with him I’m always trying to come up with some new track layout. Sometimes I’ll even lay out a new track by myself at night before I hit the sack after he’s long been asleep for him to discover in the morning. Often exploring track layouts means trying to push the boundaries and try new things. Most of the time my first idea doesn’t work and I need to step back and try again. But after some fiddling, something comes together and I discover something new.

Learning new things is like making a new Brio train track layout. You start with a vision of what you want to build. But then as you’re building it, something doesn’t go quite right. So, you get curious. You try some things out. You realize that your original idea doesn’t work. But then you see something new. This is the creative spark. But to get to the spark, you’ve got to accept the fact that your idea has a real chance of failing and try.

Of course, it’s one thing to do this while you’re playing trains with your toddler. It feels totally different to do this where the stakes are bigger like trying to figure out what you want to do with your life. But this is where a prototyping mindset can help. The beauty of a prototype is that being a rough experiment is an explicit goal. A big complicated experiment isn’t a prototype.

If you pay close enough attention you’ll see the power of the prototyping mindset powers creative people from all sorts of walks of life. It’s the kernel of David Epstein’s post from a few weeks ago that argues that we need to pour out our lesser ideas to get to our great ones. It’s the idea that James Clear shares from Jerry Uelsmann’s work that the best art doesn’t come from one very carefully planned piece but rather from a thousand little experiments. It’s the message Austin Kleon preaches in his book Steal Like an Artist: “You're ready. Start making stuff.”

You’re ready. Start making stuff.

You can choose to play it safe. But there’s always a way to run a little experiment to try out something new. To get to our great ideas, we need to go through the lesser ones. And if you embrace a prototyping mindset it’s less like your voice cracking in the middle of the Super Bowl halftime show and more like putting down a sequence of Brio train track pieces that won’t connect.

Success lies on the other side of failure. The optimal number of failures is not zero.

The Book Nook

This week I started John Le Carré’s book Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor, Rich man, Poor man, Beggar man, Thief. It’s my first book of Le Carré’s that I’m reading and I’m enjoying it so far.

The Professor Is In

I think a lot about how engineers and scientists should wrestle with the impact of our work society. There is a lot that we can learn from history, if we choose to pay attention.

The educational plan for the proposal I submitted last week laid out a series of modules to help students wrestle with the ethical dilemmas that are part and parcel of our work. From my experience, much of the wrestling with ethics in courses is through a few case studies and discussions. But I think making ethics a side dish means it doesn’t really sink in with most students who learn it that way. It needs to be a thread that runs through the whole curriculum and engages students both in and outside the classroom. It’s one thing to grapple with the technical specifications of making something work or improving its efficiency. It requires an entirely different set of skills to think about how that technology will work in the world and the sort of impact it will have.

Much of my thinking on this topic has been related to the present and future impact of generative AI, especially with respect to education. But the touchpoints between STEM and society are everywhere. I’m looking forward to the release of the new biopic Oppenheimer later this month which follows the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the American nuclear physicist who directed the lab at Los Alamos which created the atomic bomb. As I prepare to go see the movie, I watched the 1981 documentary about Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project The Day After Trinity and am planning to read the book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin which is the inspiration for the upcoming Oppenheimer movie.

Leisure Line

Still trying out my experiment of sharing these during the week as Notes. You can see them all on my Substack profile here if you’re interested.

Still Life

Although in truth, it was really more like discovering it for the first time given how long my practice lasted the first time around in grade school.

Getting good at failing is one of the great "secret skills" in my opinion: learning to repeatedly fail without getting frustrated and giving up is something we should all strive for!

Thoroughly enjoyed the Brio metaphor too - I spent countless hours playing with Brio as a kid, so much so that an entire room became known as 'The Brio Room' in my parents' house!

This is super duper important, and I wish my students understood this better.