Let It Rip

A mathematical argument for building a bias toward action and a nod to a great TV show.

Thank you for being here. As always, these essays are free and publicly available without a paywall. If you can, please consider supporting my writing by becoming a patron via a paid subscription.

I'll admit it, I'm a sucker for analogies that leverage a bit of math to make a point. So it's time for a quick math puzzle. Before you groan and jump away, don't fret, it will be fun!

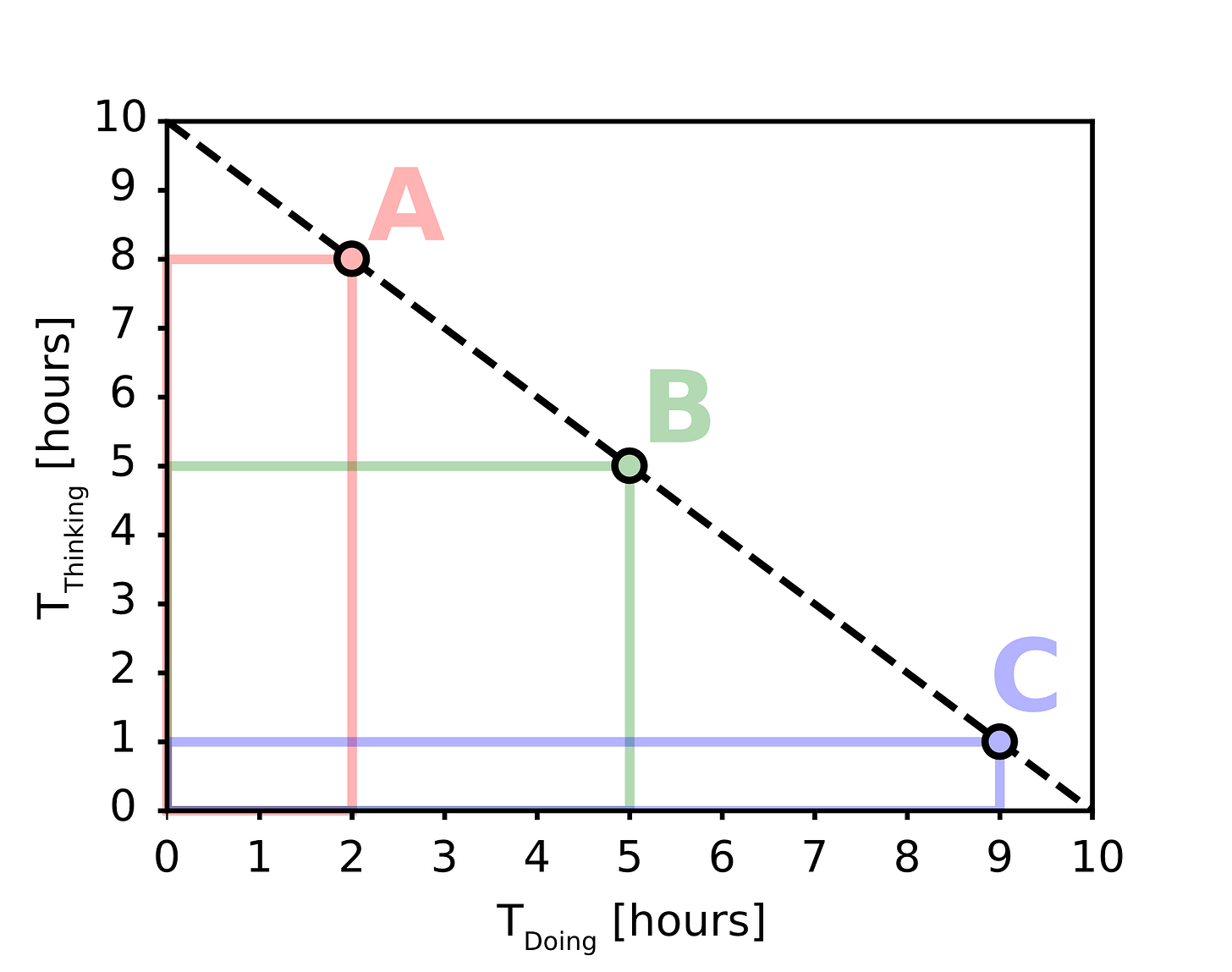

Ready? Here's the question. In the following figure, which rectangle has the largest area: A, B, or C?

The Absent-Minded Professor is a reader-supported guide to human flourishing in a technology-saturated world. The best way to support my work is by becoming a paid subscriber and sharing it with others.

Whether you did some quick mental math or just eyeballed it, I bet that many (all?) of you arrived at the right answer: B. The area of rectangle B is 25 units while A clocks in 16 and C at just 9.

What's the point? The observant among you may have noticed the axis labels. You may also be wondering what the dashed line is all about.

This plot describes the following situation. You are given a total of 10 hours to spend. It is up to you to decide how you want to divide your time between the two axes, Thinking and Doing, to maximize the area of the rectangle by choosing the optimal division of effort. The dashed line indicates the set of potential solutions that use all the available time and is given by:

You can put all your effort into one or the other axis, but as we found out from our short quiz above, neither of these choices is optimal. By leaning too far to one side or the other, we fail to maximize the area of the rectangle.

A little more math can help us understand why. More generally, we can describe the area of the rectangle as the product of the two sides.

From our problem, we also know that our total time is constrained to 10 hours. Therefore, the sum of our time devoted to thinking and doing must equal 10. Rearranging the equations a bit and substituting, gives us a new expression for the overall area of a given rectangle:

Plotting that equation gives us the curve below. Here, we are looking for the maximum value over the divisions, which is found at the peak of the curve, a 50/50 split between Doing and Thinking.

Ok, a bit nerdy…so what?

The tradeoff between thinking and doing is a part of almost any craft we pursue. For writing an essay, it might be the balance between time spent reading and writing. For an athlete working to become better at a sport, it might be the division between time spent studying film and practicing. For a teacher working on a lecture, it might be the split between editing the slides and practicing the lecture.

The point is that we often fail to realize that many of the most important metrics in life are nonlinear and the product of multiple variables. We tend to think linearly, imagining that if we double the input (e.g., spend twice as long thinking), we'll reap twice the benefits (e.g., more money, better outcomes, etc.). But this often ignores that:

The metrics we care about are decidedly not linearly related to the inputs

Our inputs are constrained (e.g., there are only so many hours in the day)

We need to break out of our linear mode of thinking and consider a more accurate (if less intuitive) model of the goal we are shooting towards, preferably one that also considers the very real constraints of our finite resources. This isn’t to say that the optimal solution is always a 50/50 split, but rather to make the more general point that the thing that counts is often nonlinear with respect to the inputs.

The Bear

Believe it or not, the reason I'm thinking about this math is the release of Season 3 of the TV series The Bear. The Bear tells the story of Carmy Berzatto, an accomplished chef who returns home to Chicago in the wake of his older brother's passing to take over the family business—a sandwich shop named The Original Beef of Chicagoland.

It's a story equal parts relatable and heart-wrenching as we watch Carmy try to navigate the pain of broken family relationships and revitalize a business that is underwater and not long for this world. Meanwhile, the return to home is unearthing his own trauma from a complicated relationship with his late brother.

I'll spare you more details to try and avoid spoiling it for those of you who haven't seen the show yet, but there's one phrase that has really stuck with me: "let it rip."

As the show progresses, we learn that the phrase is something Carmy's older brother Mikey would say to him, encouraging him to stop thinking and start doing. "Let it rip" becomes a mantra for the kitchen staff as they work together, in fits and starts, to turn the failing restaurant around. The phrase reminds them to trust their abilities and go for it, even as they are full of apprehension.

Helping our students let it rip

"Let it rip" is something we all would do well to take to heart. The truth is, most of us are too conservative on the thinking/doing curve. It is our natural impulse to overthink things, trying to consider all the angles of a problem before trying something out.

"Let it rip" is a different frame of mind. It is yet another way of highlighting the power of a bias toward action, a critical part of the prototyping mindset. It's a reminder that the optimal number of failures is not zero.

As an educator, I want to structure my courses to help students embrace failure and cultivate a natural bias toward action. One way to do this is by building assessment systems to explicitly encourage multiple attempts and reflective revision of their work. Another is by putting the nail before the hammer, curating the course content to drive toward the desired projects or problems instead of the other way around. A third is by being clear and transparent about what we're trying to do together in the classroom, explicitly motivating and justifying the power of a bias toward action.

The solution to overthinking

On the thinking/doing curve, I often find myself in the same place as you probably do: overthinking for fear of failure and what feels like too many unknowns. A simple math analogy and a beautiful TV show about a broken family and their restaurant remind us that this overthinking comes at a price.

Let’s let it rip.

Hit that comment button if you’ve got something to say.

Recommended Reading

I enjoyed listening to

’s conversation discussing her new book Fully Alive on the Trinity Forum this last week. I’ve got it on my list and hope to crack the cover before the fall.In addition to listening to her conversation, I also stumbled across this moving post on her Substack,

, where Elizabeth shares a recent experience on a trip home. It is a beautiful story of the power of simple acts of generosity. May we go and do likewise.His name was Joquone, and I will never forget him. He mothered me, in that moment, offered me mercy. He subverted the corporate systems of the motel chain in order to help a vulnerable human being. Eventually, he was able to take payment (it was the hotel’s network which had been the problem, all along). When I woke up the next morning, we hugged and high fived like old friends.

Here’s a link to the full post.

The Book Nook

I’m still working through Permutation City, so this week I wanted to highlight a shorter book I love and have been reading to my kids lately, Hello Lighthouse. It’s a Caldecott Medal winner by author Sophie Blackall.

The story is beautiful in its own right, describing what we often lose with the neverending march of “progress.” It’s a story about the way that technological innovation can displace humans and the unconsidered things we lose when we upgrade the things around us. Maybe I’ll write a full-length post on it sometime.

P.S., if you’re looking for another great book by Ms. Blackall, I highly recommend Finding Winnie, another Caldecott Medal winner which tells the true story of the bear who inspired A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh.

The Professor Is In

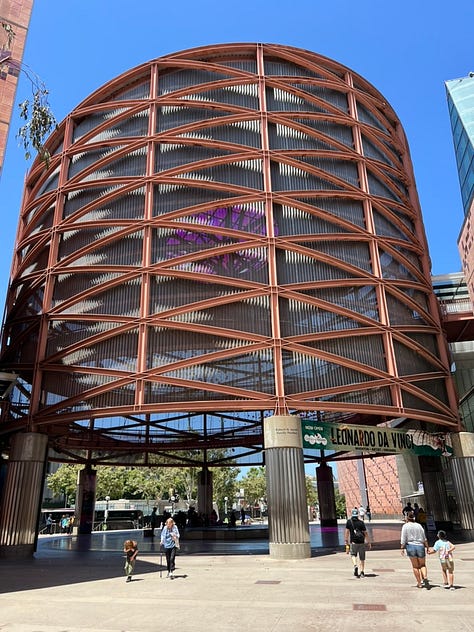

At the end of last week, I had a fun time taking the two oldest kids to the California Science Center in Exposition Park, right new to USC in downtown LA. We enjoyed exploring the exhibits and checking out the new Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center that is under construction and will house the Space Shuttle Endeavor.

Leisure Line

One thing I’ve learned: when you see Magic Spoon in stock at Costco, you had better stock up because you never know when you’ll see it again. In a move that will only fly when I’m shopping without my better half, I grabbed three double-sized boxes.

Still Life

Macro mode on my iPhone takes some of my favorite images. This time, I got up close and personal with a bee.

Amazing post! And indeed useful. Let it rip (thank you for quoting my most loved show since Stranger Things)

It is a great article as always. I am puzzled about the metric Tthinking x Tdoing. I assumed that it is a device you use to demonstrate that the non-linearity of the relation between time spent thinking and time spent on doing things. Is there any more significance to it? Can it really be a plausible proxy of the quality of the outcome of the think/do process?