There’s something special about eye contact. But we often take it for granted and with the continuous development of new technology, we’re likely to see it dwindle as part of our normal human experience.

We enter the world looking for a face

Spurred by a podcast conversation I listened to this week, I was reminded of an idea that has really stuck with me from Andy Crouch’s book The Life We’re Looking For. He writes beautifully about the universal human desire for eye contact and how we are looking for it from the moment we’re born.

Every day, in the most apparently desperate and forsaken parts of our world, as well as the most affluent, distracted, and anxious parts, babies are being born, their eyes wide open, looking for a face. They hope, without yet knowing what hope is, that they are being born into a world where someone is looking for them—a world where they will be recognized, known, and loved, a world where they will have a glorious part to play, one of the dramatis personae.

This beautiful description reminds us of the meaning embedded in the human gaze. The way we look at each other expresses care, attention, and the desire to know and be known.

Eye contact is becoming increasingly rare in our technology-mediated age

Eye contact has been in our cultural conversation lately in a few different areas. Along with many other reflections on our need for community, we recognized in the midst of the pandemic that eye contact, or at least the simulation of it, was a big piece of what felt draining about our Zoom calls.

Although we can see each other’s faces on the screen, we’re not actually looking at each other. In fact, the design of our devices and the placement of the cameras on them means that we can either stare at the face on the screen or into the camera, but not both. Even if we’re looking at the person’s eyes on the screen, the image that they see looks like we are looking elsewhere. To make matters worse, even if we can tell that the people on the other side are looking at their screens, we never quite know: are they looking at us or just scrolling through their email or the news?1

Eye contact and the metaverse

Another place where the idea of eye contact is relevant in the world of tech recently is in virtual and augmented reality, the realm of Zuck’s increasingly abandoned vision of the metaverse. (Ironically, it seems that he’s pivoted from the metaverse to the physical world, preparing to fight Elon in a literal cage fight and trading salty missives online about their competing social networks.2) In the metaverse, we all engage with each other in a new virtual world mediated by immersive screens. Here eye contact is completely eliminated, replaced with a simulated version of it.

The issue of the eyes is so important for AR/VR goggles that it becomes a central technical challenge to solve. Eye contact takes top billing in Apple’s new flagship product which they announced earlier this year, the Apple Vision Pro. As you navigate to the product page, the headlining feature as you begin to scroll shows how the goggles are designed to look as if you’re peering through them. In fact, nothing of the sort is happening.

What you are actually seeing is EyeSight. Aptly named as most Apple products are, with a catchy title in PascalCase, EyeSight promises to solve the problem by creating a virtual version of the part of your face covered by the goggles, displaying it on the front of the goggles. The screenshots from their website below show you what it looks like.

Technologically, this borders the magical. I can only imagine the amount of computational power and imaging hardware needed to pull this off as seamlessly as it seems Apple has done. It’s a marvel of engineering and a testament to the firepower of the design and engineering teams at Apple.

And yet, after the dust settles from the initial sense of wonder at the technological marvel, I can’t help but wonder if it’s anything more than a parlor trick. Is EyeSight really categorically different than talking to someone on Zoom or FaceTime? Maybe we’ll be able to better fool our brains and the brains of the people around us into thinking that we are looking at each other, but we’re not. Instead, we’re going to be staring at a super high-resolution digital display inside the goggles mediating our experience of the outside world. And in turn, the people we are looking at through our goggles will be seeing us through theirs. Perhaps this is the ultimate version of having eyes but failing to see.

This is a future without eye contact. Is that really the future we want?

Teaching and the power of eye contact

All this thinking about eye contact has me thinking about its value—paying attention to the ways in which I so often take it for granted and thinking about how I want to embrace it more fully this semester. I’m specifically thinking about the power it has in the context of my work in the classroom with my students. As more and more of our interactions are mediated by technology, the power of even simple opportunities for human connection, whether making eye contact with students in class or sitting down together over a meal at lunch, will become increasingly special and needed.

One of my core values as a faculty member is embracing the importance of relationships, both with my students and colleagues. Deepening relationships occupies a lot of my thinking as an educator as I search for ways to come alongside my students on their educational journeys as they seek to discover who they are, who they want to become, and the good quest that they want to pursue over the course of their life. I’m increasingly convinced that eye contact has a significant role to play.

In a world where we are increasingly looking to machines to entertain and even to care for us, what will we leave behind when we replace the gaze of another human with cameras and screens?

Got a comment or thought to add to the conversation? I’d love to hear it.

The Book Nook

I just recently finished The Sabbath by Abraham Joshua Heschel. I really enjoyed this book and found Heschel’s understanding and argument for the practice of the Sabbath to be deeply thought-provoking. I found it to be especially relevant as many of us wrestle with the struggle of integrating our work with our life and dealing with feelings of burnout.

A few passages that resonated:

Yet to have more does not mean to be more. The power we attain in the world of space terminates abruptly at the borderline of time. But time is the heart of existence.

We must not forget that it is not a thing that lends significance to a moment; it is the moment that lends significance to things.

The meaning of the Sabbath is to celebrate time rather than space. Six days a week we live under the tyranny of things of space; on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to holiness in time. It is a day on which we are called upon to share in what is eternal in time, to turn from the results of creation to the mystery of creation; from the world of creation to the creation of the world.

The Sabbath as a day of abstaining from work is not a depreciation but an affirmation of labor, a divine exaltation of its dignity. Thou shalt abstain from labor on the seventh day is a sequel to the command: Six days shalt thou labor, and do all thy work.

On the Sabbath we live, as it were, independent of technical civilization: we abstain primarily from any activity that aims at remaking or reshaping the things of space. Man’s royal privilege to conquer nature is suspended on the seventh day.

There is much that philosophy could learn from the Bible. To the philosopher the idea of the good is the most exalted idea. But to the Bible the idea of the good is penultimate; it cannot exist without the holy. The good is the base, the holy is the summit. Things created in six days He considered good, the seventh day He made holy.

Inner liberty depends upon being exempt from domination of things as well as from domination of people. There are many who have acquired a high degree of political and social liberty, but only very few are not enslaved to things. This is our constant problem—how to live with people and remain free, how to live with things and remain independent.

Time is man’s greatest challenge. We all take part in a procession through its realm which never comes to an end but are unable to gain a foothold in it. Its reality is apart and away from us. Space is exposed to our will; we may shape and change the things in space as we please. Time, however, is beyond our reach, beyond our power. It is both near and far, intrinsic to all experience and transcending all experience. It belongs exclusively to God.

The Professor Is In

The fall semester is underway! It’s been a crazy start to the semester trying to get everything fired up and running smoothly, but so far so good all things considered. Thankful to have a whole new set of students in my classes.

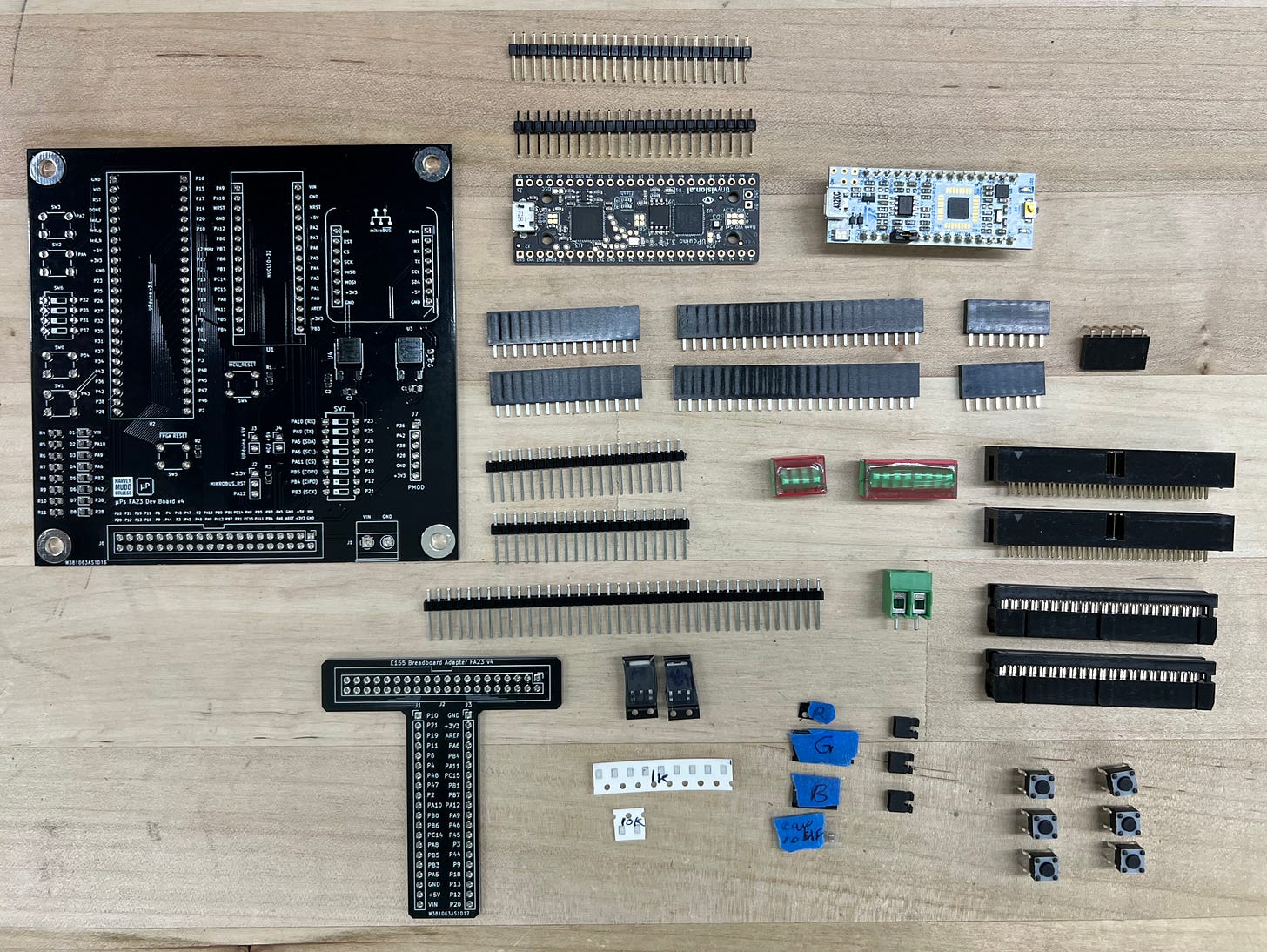

Below you can see a photo of the components in the kit for my embedded systems class, E155. The big board on the left-hand side a motherboard I designed to host the FPGA and MCU development boards. It allows you to connect signals from the boards together without the need for any external wires and also has some other LEDs and buttons on the board to act as additional input and output sources. The smaller t-shaped board on the bottom is a breadboard adapter that connects via a ribbon cable to allow for easy breadboarding, inspired by the Raspberry Pi Cobbler board.

This week students in E155 will work on soldering their boards together and testing out the components. Fun to get some hands-on work from day one!

Leisure Line

Y’all know that I’m a big Cal Newport fan. I’ve always found his advice about time blocking to be useful but have always used a spreadsheet or a standard notebook to do it. The new version of Cal’s Time-Block Planner just came out a few weeks ago and I decided to give it a try for this fall. It’s got some subtle upgrades from the first version, headlined by the spiral binding which allows it to lay nice and flat. So far I really like it. Any excuse to pull out my fountain pen during the day is a good one!

Still Life

The tomatoes are going gangbusters in the backyard. These ones are still a ways from being ripe, but are growing quite nicely.

Although apparently, the fight is off. Maybe they’ll fight in VR now?

"Although we can see each other’s faces on the screen, we’re not actually looking at each other. In fact, the design of our devices and the placement of the cameras on them means that we can either stare at the face on the screen or into the camera, but not both. Even if we’re looking at the person’s eyes on the screen, the image that they see looks like we are looking elsewhere."

This cleared up a question I didn't know I was holding; thank you!

Good points about eye contact being an important part of the puzzle. With Zoom or other video chat, I always feel like some of the body language comes through, but not all, and that's one more differentiator with in-person conversations (still my preferred method when important and when available).